Welcome to 2023’s edition of “Some Games I Played in [Year] and What I Thought Of Them”! This has been a very busy year for me – much of the time was spent applying for, and subsequently getting (phew!), both promotion (to “Senior Lecturer”, roughly equivalent to Associate Professor in North America) and tenure at my university, as well as writing and editing a book – simply called “Twitch” and soon to be published in this series – that represents the culmination of almost an entire decade (!) of research into the site.

Nevertheless, despite all of this I was also able to release Ultima Ratio Regum 0.10 earlier in the year, as well as an update just a few months ago, and for the first time in years I’m keeping up monthly or three-weekly blog updates, so overall I’m really very happy with how things are moving along :). A busy year, but by my count I played a total of twelve games this year, and the usual mix of old and new, indie and blockbuster, and so on. I’ve written up a little review of each of them, and saved my game of the year (which for me means game I played this year, not necessarily game released this year) for the very end. Hope you all enjoy this write-up, and as ever, do leave your thoughts on these games in the comments, or thoughts on games you’ve played this year, or that I ought to try next year!

But yes, without further ado, let’s get started:

La-Mulana 2

You know something, friends? I really thought this was going to be my favourite game of the year.

Last year’s “winner” was the original La-Mulana (or rather, the original remake, or the remake of the original, or… whatever it is) which absolutely blew me away with its astonishingly cryptic puzzles, incredible confidence in the player, and stunning artistic and musical direction. The sequel is also an excellent piece of work, but not quite to the same level. The first surprise comes when the game begins more easily and less harshly than its predecessor. This seems a clear attempt to appeal to new players and to prevent people being turned off by how astonishingly uncompromising the start of the previous game is – but somehow this just doesn’t convince. Are there going to be enough players attempting this game without having tried the sequel to make this decision choice appropriate? I’m not sure, and for a returning player who was coming to the game after the peak challenges of the first game, the early sections of this game felt bizarrely trivial, especially one particular puzzle which gives the player so many hints – one of which literally just tells you what to do – that I found myself alarmed by whether this game was all going to be trivial. Happily the game does quickly ramp up to the same kind of difficulty as the first game, but I would also say the hardest of this game’s puzzles (activating Brahma, solving the underworld gates, getting the cog of antiquity, etc) are all a little less challenging than the hardest of the first game’s puzzles (figuring out where to get / use the mantras, the Endless Corridor’s number riddle, flooding the Tower of the Goddess, etc). They are nevertheless very demanding though – but whereas the first game I needed three hints to complete it, here I needed only one (the infernal fiend and colossal dragon puzzle, for those who are wondering). The art and music remain outstanding and when coupled with the puzzles and the overall presentation of this mad, sprawling world, the sequel is a delight to plunge into.

The issues with the game however are significant, and essentially stem from the fact that the developers seem to have leaned more strongly into the “platformer” than the “puzzle” aspects of the first game in designing this sequel. Given that it is the cryptic puzzle elements of the first game which made is so famous and so infamous, this is a very peculiar decision. The main way this manifests is how the game’s bosses and minibosses have largely been made more obnoxious – I think in a poorly executed attempt to simply make them more challenging – and many have transitioned from being difficult to merely being unpleasant and frustrating to encounter. This is not even a fun or provocative frustration of the sort one might find in an early Souls game, but is merely frustrating and nothing else. Two of the bosses in particular are so obnoxious as to almost baffle the mind, especially after I learned that one of them had previously been even worse before being patched to make it just slightly more acceptable. These are nothing but annoying and tedious road-blocks entirely devoid of enjoyment, and simply demand that the player grind through them in order to get back to the actual game. Other disappointments came from one area which was essentially an inferior repeat of an area from the first game, and the choice to make the final challenge before the final boss into obnoxious and frustrating dungeon rather than a hugely difficult and cryptic puzzle, again really weakening the game’s conclusion and leaving something of a sour taste. Other aspects are wonderful and novel – such as the way the game has you explore what little remains of the first game’s ruins and presents them, hilariously, as having been essentially transformed into an archaeological theme park – but ultimately the sequel is a flawed masterpiece instead of merely a masterpiece. The original is never anything less than a challenge to get through, whereas although the sequel is often a challenge, it is sometimes a slog, and those parts prove deeply frustrating and really reduce one’s enjoyment of the whole thing. I still loved my time with it, but it’s not going to replace the original any time soon.

Horizon Zero Dawn

Why, given my strong dislike of open world games and my extremely negative experience with large parts of Elden Ring, did I then go and play Horizon Zero Dawn? It’s a good question, dear reader, and one that I don’t have any clear answer to. Perhaps it’s because the visuals and art direction seemed very compelling and distinct; perhaps it’s because it’s trying so specifically to be an open world game and therefore I thought it might be more tightly designed as a result; maybe I just enjoy the post-apocalyptic (although I think if we’re being really specific the HZD setting is more “post-civilization”?) setting so much that it was worth a shot? I’m still not quite sure, but either way I decided to give this one a try, and I’m fairly glad I did. I can’t say it was the greatest piece of work I’ve ever played and some of the open world elements did grate with me, but as soon as I learned to ignore them, focus on the main quest, and crank the difficulty up to maximum from the moment I started in order to make the combat into the main challenge, I actually really enjoyed this game! The setting is really compelling and does a great balance between the natural world and the technological aspects, and I’m always a fan of imagining human civilizations that might emerge in the distant future. The combat seems pretty tight and enjoyable and I thought the voice acting was generally pretty strong. The sound and music design were both excellent, and I did sometimes find myself really settling back and just taking the time to enjoy the world and the ambient behaviours of the various robot creatures. Some of these first encounters were really striking, and definitely stood as some of my highlights from the game.

However, after getting around a quarter of the way through, I actually departed the game and haven’t yet returned. I think I likely will at some point, but at this particular moment in my life I just don’t feel all that inclined to commit the time and effort, even on the understanding that I’ll be skipping a lot of the optional content and really just focusing on the world and the core narrative. Too much of the game felt too familiar in the abstract sense, by which I mean, there’s just so much here that’s in every other open world game adopting the now-normal Ubisoft model for these sorts of worlds. Lots of collectible things, side quests all over the place, a map absolutely full of minor points to visit… I did generally overlook these and focus on the main world, and I acknowledge that this game actually did a better job of narrative justification for these than some other games, but it still definitely got in the way of my enjoyment. I also found much of the game to be far too scripted and sometimes predictable – there’s an early scene where a bunch of raiders or bandits attack an important cultural event for one’s own tribe / nation, and it was so clear something like this was going to happen, and then it played out in a fairly predictable manner after that. Ultimately all the novelty just didn’t seem to be enough to outweigh everything that was familiar and predictable here; and while I realise this is a game that in my younger years I would have been far less critical of, I am now sufficiently old, withered, tired and cynical, that these repeated elements just cannot any longer get a free ride from me. I don’t think it’s impossible that I’ll come back to Horizon Zero Dawn, though for now there are other big, blockbuster games that demand my attention first.

Cannon Fodder II

Back when the United Kingdom actually mattered in digital gaming (i.e. ~1994) Cannon Fodder II was released. This was one of the earliest PC games of my childhood I can remember, alongside things like Chip’s Challenge, Jezball, Rodent’s Revenge, and a procedurally-generated text-based adventure version of the Three Billy Goats Gruff fairy tale my father and I played in MS-DOS which I have never been able to find again (yet I know it exists and I did not imagine it). Cannon Fodder II, however, gives you control of a squad of soldiers who find themselves first in a Middle-Eastern setting before then setting off for medieval Europe, outer space, and various other bizarre locales. The graphics are simple by modern standards but actually pretty charming, and later levels give the player a range of different vehicles and weapons with which to battle their enemies. The base gameplay – you have a little squad of people who can collect weapons, split into other squads, the weapons all have various abilities and advantages and disadvantages, and the levels are essentially like puzzles to be solved with the finite resources you have – is actually very good, at least conceptually. The levels quickly start to require a surprising degree of strategy, even if some of this can require the player to magically know what’s coming next before it actually happens, and the difficulty ramps up with alarming speed. Playing as an adult I quickly got further than I had a child but even now I found my progress slowing down pretty soon as the levels got larger, more complex, less forgiving, and more hectic. I decided to revisit it this year and I did actually enjoy my time with it for the most part, as the game is pretty unusual and distinctive, has a quirky charm to its visuals and sound design, and plays with just a tiny bit of quasi-permadeath (think Darkest Dungeon, not NetHack).

The game has two main issues however. Like a lot of early games in general, and early strategy games or games like this which are strategy-adjacent, there simply just aren’t too many objectives. Last year I replayed the original Grand Theft Auto, and in-between bouts of crushing pedestrians and being genuinely astounded by the raunchiness of its humour, I couldn’t help but notice how few missions there are. Drive to X, walk to Y, shoot Z – that’s literally it. Cannon Fodder II suffers from a similar issue, since even if you sometimes need to employ at least a reasonable amount of grey matter to figure out how to kill everything on screen using the paltry resources you’ve been given, the goal is still essentially always kill everything. There aren’t any other objectives, and this means the game does get repetitive pretty fast. The second problem is that the controls are truly dire by modern standards, with the mouse simultaneously letting you look and aim and shoot but not do just one of them, the game requiring quite a bit of compatibility fiddling to even work at all (and then only in a small window), and inputs from my mouse controls sometimes just being delightfully ignored by the game. Your squad of troops sometimes controls like an octopus whose movement is being battled over by its eight different arm-brains, and although the player has a lot of what we might think of as high-level control over your soldiers, precise controls and precise manipulation are not exactly the game’s strong suit. I honestly decided to call it a day less because of the difficulty – though it was getting tough after a couple dozen missions – but more because it was just such a chore to get my stupid little squaddies to actually do what I wanted them to, particularly in missions with very little flexibility and very little space between life and immediate death. That said, I still think the core concept is actually really interesting, and we see similar things being done in more recent games like X-COM and the like. If only the controls were not quite so excruciating…

Into the Breach (Advanced Edition)

Much like FTL, Into the Breach is one of my absolute favourite roguelites, and one that I’ve put a tremendous amount of time into. I was previously very close to clearing every island number with every squad on hard mode (yes, I do like this game) but then the Advanced Edition came out. The developers – as with their previous game – of course deserve massive credit for releasing this expansion entirely free of cost, as that’s an incredibly rare and incredibly cool move, especially as I would gladly have paid many tens of dollars for all this new stuff. The expansion adds in a ton of new stuff, and it’s all great. The new squads are all interesting – though I have seen a couple of modded squads made by players which strike me in a couple of cases as being potentially more interesting – and I’ve enjoyed playing with all of them, although I don’t think the challenge levels of the various squads are exactly equal (though in a singleplayer game this obviously doesn’t have to be a bad thing). The vast range of new weapons is also excellent, adding a ton of variety to a game that I had pretty much exhausted and offering a range of interesting new strategies and synergies with the already massive variety of mechs, pilots, weapons, and tactics. The new enemies are all interesting and varied, and the new bosses are a really valuable addition. They bring a ton of extra variety to the game when you’re someone who has already exhausted or come very close to exhausting the base game, this is a fantastic addition.

They’ve also gone back in and added a number of new skills and mechanics to the game, and these bring some really nice extra variation as well. Some of the new mechanics, such as the ability to crack terrain and also the ability to get a “boost” on a mech that will increase its damage on its next attack. Games like this always succeed on maximizing the number of possible permutations and scenarios it can throw the player – this is true of course for roguelike-y games in general – and I’ve been really pleased by the game’s ability to continue producing scenarios and permutations that I hadn’t seen before, and hadn’t necessarily anticipated. There are definitely still a few weapons and skills that don’t really have a great deal of use, and one particular mission (the malfunctioning shield generator on the ice island) seems markedly harder than any other mission in the game, but these incredibly tiny things are the only minor blips in an otherwise beautifully polished, smoothed-out, and compelling additional experience. I actually haven’t yet tried this new difficulty implemented above “Hard” mode but I’m looking forward to doing so in the coming year. I don’t think I’m going to get every squad and every island number on that difficulty as well, but I’m definitely going to give it a proper shot and see what I can do there. An already great game has been made even stronger, and it has been a huge pleasure this year to come back to it and challenge myself with it again.

Environmental Station Alpha

Having played and been blown away by my game of the year (don’t scroll down!) I decided to look at some of the other work produced by the same team (this is a clue, for those in the know, about what my game of the year might be). I was disappointed several years ago by Baba Is You – which feels not as clever as it seems to be on the surface, and something that really trades off the idea that programming and code-logic are inherently the most fascinating things in the world (which they are not) – but Environmental Station Alpha appeared to be a much more traditional Metroidvania with lovely graphics, a great soundtrack, and apparently some fearsome bosses and extremely challenging hidden puzzles of the La-Mulana or Outer Wilds type. I have to say that most of the game I absolutely loved. The difficulty level was high but not absolutely ridiculous, the world was indeed very beautiful and varied, pleasingly mysterious and also able to reward the observant player with some very well-hidden secrets, extra items, and the like. It also left quite a lot to the player’s mind to figure out and deduce in terms of how the world map is constructed and how certain pieces of the world interact with each other, while the bosses were indeed a particular highlight, all being difficult, visually exciting, and accompanied by fantastically intense music. Like roughly 40% of the world’s entire human population I am also excitedly waiting for the release of Hollow Knight: Silksong and I am pleased to say that Environmental Station Alpha did a great deal to keep me going in these wilderness years. That said, though, one recurring and frustrating issue was how acquiring one type of key often just led to an area that would immediately require another key – this seems like a key design point to avoid in Metroidvanias in order to limit frustration. Aside from that, however, my couple dozen hours with the core game I found entirely delightful, a good challenge, and very tightly designed and enjoyable.

However, the real disappointment for me here was the end-game content, and this came in several parts. Firstly, it has long been a source of frustration to me that so many science fiction stories, or rather stories that initially present themselves as being science fiction, for some reason feel obliged to add some spiritual or mystical elements into their narrative. Around half-way through the game I encountered a number of sort of ethereal or ghost-like enemies in a “temple”-type area and this began to bode ill, and sure enough the secret hidden stuff at the end of the game simply got weirder and weirder, and not in a compelling Lovecraftian kind of way. Part of this weirdness also became at least somewhat fourth-wall-breaking. In some cases (and some games) this can work extremely well, but here it felt extremely jarring; the game had done so much work to make the Station appear so very solid and grounded, and then having it gradually become less and less realistic, increasingly strange, and increasingly willing to play with the nature of the game itself, really didn’t sit well with me. The second issue was that the end-game puzzles were simply not as interesting as I had hoped. A source of particular frustration in this regard was an end-game language puzzle where one had to translate an alien script into English to get various clues. I did this without actually finding the key in-game you’re meant to use (this is no great brag – deciphering an English-language substitution cipher without a key is not exactly challenging!) but what became intensely annoying was the fact that more and more things in the end-game needed translation, even though these end-game areas I could not have accessed without having previously cracked the translation. Every time I was forced to get out my list of letters again to translate another message, even though I had already demonstrated my solving of the language puzzle, I became more and more frustrated. Eventually I actually just gave up as I wasn’t enjoying the end-game cryptic puzzles, the meta / spiritual-y weirdness of the secret areas didn’t give me personally any reward for cracking these puzzles, and I just lost motivation. I’d rate the core areas of Environmental Station Alpha extremely highly, as a real delight, but the secret end-game stuff was sadly a significant let-down for me.

Sonic Dreams Collection

Well, this is beyond doubt the funniest game I have ever played. It is hard to believe something this witty, this satirical, and this spot on in its satire, exists.

I’m not really sure what else I’m meant to say here.

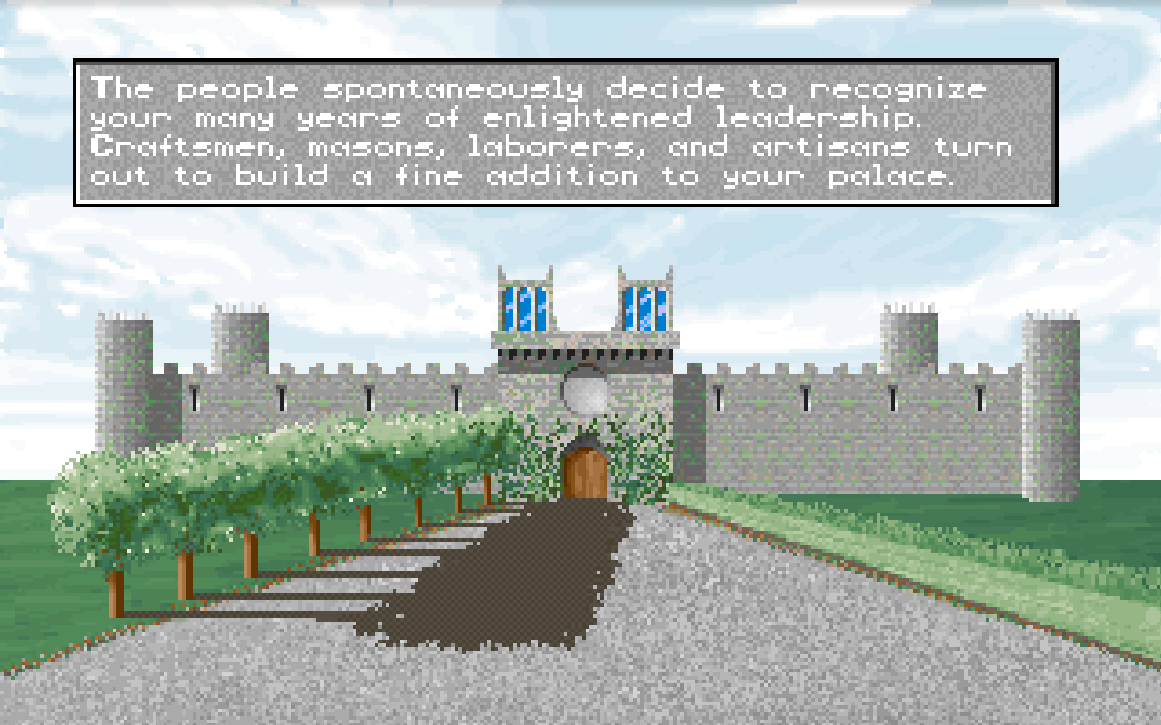

Civilization

Something this made me decide to play Civilization I again. What influenced this decision? I honestly cannot say – I just found myself with a desire to go back and check it out. I have to say that I really enjoyed my time with what I found! It’s a really very solid first game in the series – there are loads of buildings and wonders of the world, a fair number of units, the graphics are pretty basic but actually very charming, and there’s a reasonable level of strategy. It does fall into a trap that many Sid Meier games fall into, which is that technology generally advances so rapidly that one doesn’t actually get a tremendous amount of “play” with each set of units before military technology changes render them obsolete. In Alpha Centauri I always play with slow technology for this reason, and I really wish here that the technologies advanced less rapidly for the exact same reason. Importantly, though, for the first time in ym life I was able to actually win on the middle difficulties, and with a bit of effort I think I could secure a win on the upper difficulties too. One thing about this first game that really stands out is the palace mechanic – as in the picture above – in which upon reaching score metrics your citizens decide to reward your years (decades, centuries) of excellent (dubious) rulership (bumbling) with an addition to your palace. Choosing what additions to put into your palace is a really satisfying and gratifying little mini-game and one really gives a sense of achievement and progress that is distinct from other metrics of achievement in the game.

A number of rather amusing things happened in my play of this game, though. For starters I realised that as a child I had no idea what changing your nation’s political system did, and so I never changed it, despite the fact that literally half of all in-game resources can only be accessed by the more modern political systems, and so after part-way through the game (i.e. when those systems become available) I was always playing at a tremendous disadvantage on against the AI. This is one of those discoveries – especially when I think back to how unfathomably hard I found the game as a kid – that makes one either laugh or weep, so I elected to laugh, even though inside, dear reader – I wept. I also finally came to actually understand how the various improvements on tiles work and hence some very clearly more optimal ways to construct my civilization, as well as finally partly figuring out how the happiness / rioting mechanic works. Mechanics about happy or unhappy citizens in a city or base have always been something a little bit obscure in some of the earlier civ games (looking also at you here, Alpha Centauri, with your indecipherable citizenry screen) but I think I was able to get a grip on it here. I was also struck by how difficult it is to claw one’s way back after falling behind, but also how weirdly strong the AI is, especially in terms of combat and moving pieces around the map. It is ultimately a very basic game compared to what came later, yet in other ways it is one with a surprising amount of depth and detail, and even though two playthroughs always wind up looking very similar – generally a weakness of these sorts of games – it’s really not hard to see how and why this took off so thoroughly when it first came out.

Those political systems, though. Urgh.

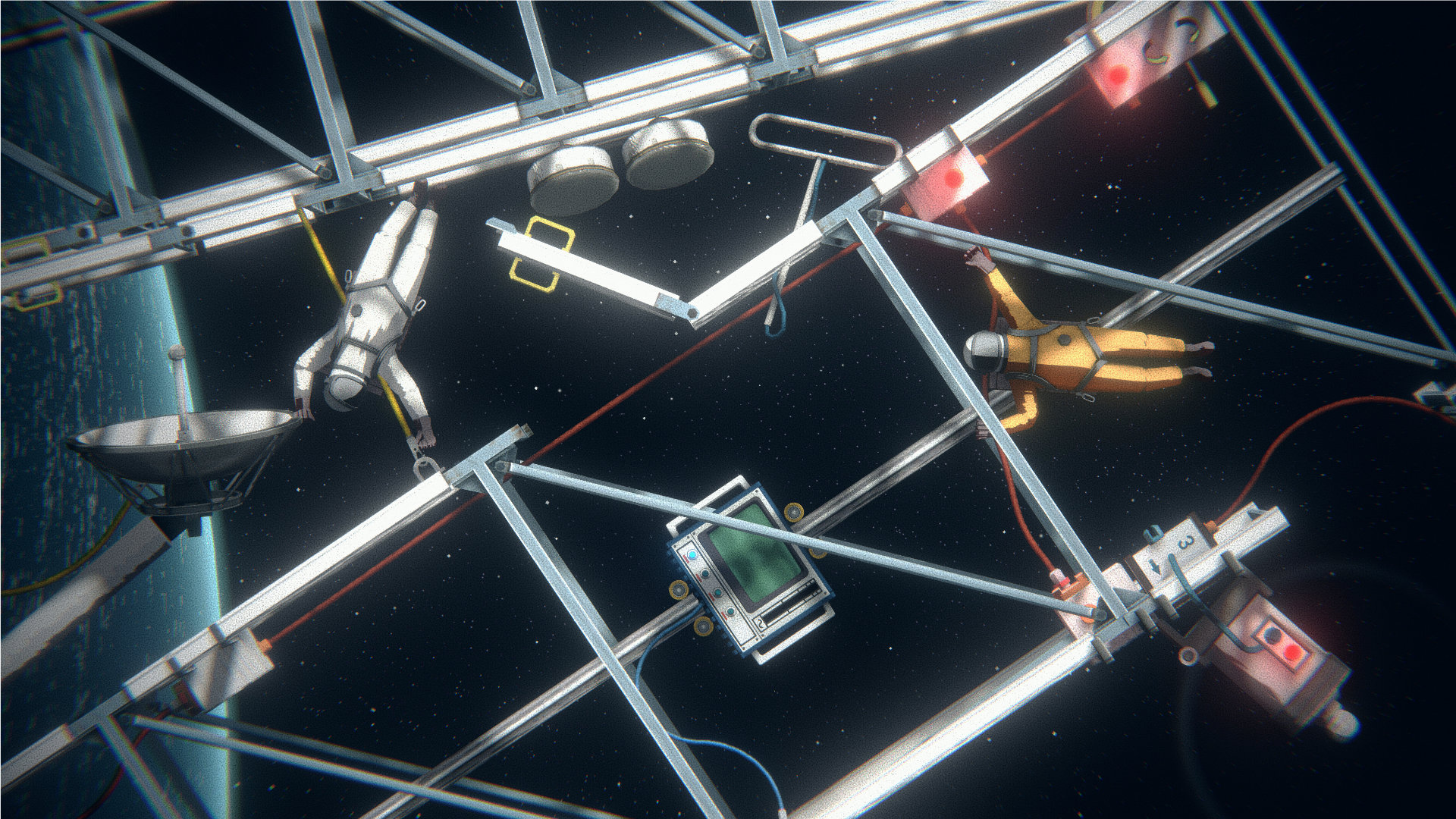

Heavenly Bodies

Well, what a delight this was! I haven’t played too many modern physics-based games – maybe all those low-effort physics-based asset flips on Steam turned me off them? – but this was a real pleasure. In Heavenly Bodies the player finds themselves and a friend tasked with doing a number of operations and tasks in space, which would be extremely mundane and easy to accomplish when under the effects of gravity (and with a control system that is, I think, rather designed to be amusingly difficult, with each limb having its own articulation) but are remarkably challenging when floating and bumbling around in low-earth orbit. This might mean connecting certain cables in your space station or spacecraft, growing some plants, aligning a satellite dish, mining asteroids, things of this sort, and the potential for disaster – generally involving accidentally flinging something important out of your ship or into an area you cannot easily reach – always remains alarmingly high. The control system does deserve its own mention, as it simultaneously contrives to be highly precise and incredibly unwieldy – it puts one in mind of things like Getting Over It – and I really enjoyed the process in each stage of working out the best way to address oneself to the task at hand. The graphics are unusual and the grainy effect is novel but I really liked how the game looked, and it really gave a sense both of the solidity of the game world but also the slight weirdness / strangeness of being off in outer space.

The game also has a number of lovely little details, which I always appreciate in games. In each mission you are granted access to a manual, which is presented as an actual ring-bound paper manual, and part of the challenge is actually in deciphering the visual material within the manual. I don’t think I’ve ever seen another game that makes an IKEA-style “how to do X” manual into an actual gameplay element, but it’s really charming and quirky, and I really enjoyed trying to relate the pieces shown in the manual to the pieces available in the game world. These sorts of game mechanics – comparing X to Y where both X and Y depict the same thing, but differently, rather like treasure maps in a certain in-development roguelike – are always very interesting I think, and I very much enjoyed this unexpected but well-developed extra element of the game. The pieces of space travel history one can find in each level as hidden collectibles is also a nice tough, and overall the aesthetic is very pleasing. Despite being set in orbit in a frozen airless void, it’s actually a very warm and wholesome feel the whole game has, and it gives a sense of comfort and ease as you’re drifting around these space machines doing your space business. I would have liked even more to the game than what there is, but what is here (it’s a game on the shorter side of things) was a lot of fun, and a rare example for me of really enjoying a physics games.

Enter the Gungeon

Although I haven’t played Rebirth, the original Binding of Isaac was – along with FTL – the other first roguelite or roguelikelike or modern roguelike (I prefer this term, personally) that I played around a decade ago. I absolutely loved it from the grotesque and twisted aesthetics and story, to the speed and smoothness of the gameplay, to the sheer variety of possible playthroughs, to the core combat, to the number of clever strategies that the more advanced player could develop for really squeezing every bit of potential value and character-building out of each playthrough, to the sometimes quite complex strategic choices one had between Item X and Item Y. Even after I’d 100%’d the thing I kept playing, and when Enter the Gungeon came onto my radar as an Isaaclike – many roguelikey elements, bullet-hell-type gameplay, a lot of replayability, a very high level of challenge – I was immediately interested. As with so many games it was then a couple of years until my mental processes aligned perfectly to tell me that now was the time to play it, but that did indeed happen in 2023, and so 2023 was for me the year of the Gungeon. Or, rather, it was a couple of weeks of the Gungeon.

I have written before about how roguelikes and roguelike-y games often live or die on the variety of their early-games, especially when you’re learning the ropes. If the opening sections of a roguelike are always varied and interesting, dying and restarting is far less painful than if the early game is highly predictable and routine and upon death one simply has to slog through everything again to get back to roughly where one was before. At least in my reading from my dozen or so hours, the early sections of Enter the Gungeon appeared, regrettably, to be very same-y. On my first playthrough I made it to the fourth level of the Gungeon (no idea whether this is a strong or weak first attempt) but after that, the first three levels felt very tedious on each subsequent playthrough; there was little there to challenge me but also little variation in what I was finding, especially when compared to the game’s obvious inspiration, i.e. The Binding of Isaac. This in turn led to me being rather less cautious and rather more carefree in these early stages, resulting in some frustrating deaths that then further got on my nerves by sending me again right back to the start. When compared to many of my favourite classic or modern roguelikes – NetHack, Dungeon Crawl Stone Soup, FTL, Isaac, The Curious Expedition – I do feel these early sections of Enter the Gungeon really lacked much in the way of procedurally generated variety, and this is something long-term readers will recall was a complaint I levelled at Nuclear Throne as well a few years ago. The opening to your permadeath game simply has to be varied and interesting, otherwise you’re going to lose your player when there are regular deaths to be navigated. Much like Horizon Zero Dawn it’s not impossible that I’ll return to the Gungeon in the future, but for now I feel I enjoyed what I saw, I was very charmed by the graphics and the creatively and the setting, but the degree of procedural variation (especially in the early levels) was just too low for me to keep playing any longer.

(But if the early-game variation increases significantly as one unlocks more, for instance, then please do let me know in the comments, and maybe I’ll give it another try…)

Hollow Knight

This is the second time I’ve come to Hollow Knight – I first played this in 2017 or 2018 when I was living in Edmonton in Canada. Back when I first played it I found myself absolutely mesmerized by this beautiful and whimsical insect kingdom, with all its various species, its histories, its architectures, its hidden places and strange magics and charming and quirky NPCs (I’m generally not a fan of “quirk” [?] in games and so I’m intrigued to see what I think of Undertale when I finally get around to playing it, but I love the characters in Hollow Knight), while the combat was sufficiently taut and challenging that it makes a wonderful contrast against the game world. This is far from being a trivial game, with the platforming and the combat both being very demanding of skill and practice. Nevertheless it really was the world and characters who stuck with me, including many of those which (I’ve since learned) are particularly well-loved by the wider community around the game. Yet towards the end of the game my enjoyment definitely wavered, as the story became darker and stranger and more and more of a clash with the rest of the game world, and I just lost interest in any of this weirder stuff that seemed so out of tone with the rest of the game. It reminded me of when a sequel to a game or film doubles down on the aspect of the previous that nobody likes; was anyone playing Hollow Knight for weird dark lore?! I… don’t think so?

Anyway, I came back this year and gave the whole game a second playthrough. It was a lot of fun! Overall though, I found that little is unchanged. The parts I love – most of it – I absolutely love, and these sections of the game are a true delight. It’s so charming, so full of detail, set in such a novel and fresh setting, fairly challenging (though inevitably less on a replay), so beautifully drawn, with a fantastic accompanying soundtrack, and so vast and expansive and so full of surprise and care and attention… and yet let down in the later-game so heavily by its reliance on a surface-level knock-off of Dark Souls lore, its corruption of this delightful and whimsical insect kingdom with weird dark nonsense, and a late-game humorlessness that totally baffles the mind when we contrast it against everything else in the game. I haven’t really heard many other people expressing this feeling of a clash, but to me it really is like there are two games here, one big one and a smaller, far worse one, nestled within the bigger one. The bigger one is fantastic but the other hidden game is just infinitely more disappointing. With Hollow Knight being still wonderful and still frustrating, I remain excited for Silksong’s eventual release, but I will be going in a little more warily next time around, knowing I will find a world of beauty and charm and magic, but that a second and far less compelling world might well be hiding underneath its wonderful surface veneer…

Don’t Starve Together (continued)

We now come to my second-place finisher from this year: Don’t Starve Together. This first came up on my gaming list last year when I rated it highly, impressed by its ability to pull me into a genre (survival games) that ordinarily leaves me completely cold. The artwork is fantastic, of course, but the gameplay is nicely challenging, the permadeath element gives a real consequence to what you’re doing, and what I’ve particularly enjoyed – after reaching a point where I can consistently survive indefinitely – is figuring out all the world’s secrets. There are lots of small puzzles, riddles, hidden interactions between various elements of the game world, lots of what we might essentially think of as hidden quests, and also a lot of satisfying ways to further optimise one’s base, one’s resource gathering, and things of this sort. I’m generally not particularly excited by games with open complex systems that enable one to develop a range of different approaches – like the Zachtronics games, for example – as I always find myself thinking the degree of required effort is so high that I might as well just put that effort into actual programming rather than games that resemble programming, but: I really enjoy this aspect of Don’t Starve Together. Each time I figure out a way to create an effective farm for a new creature, for example, or a better way to efficiently gather a resource, I feel very satisfied with the accomplishment, and the pacing of the game is so well done that these discoveries always allow one to do just that little bit more than one previously was.

What is also striking is that my first playthrough to get past around day 70 is now on day 1245, and I can truthfully say that on every single play session (normally a few hours) I have found something new. Sometimes it’s something major – a new boss, for instance, such as the giant bird Malbatross creature I have discovered in the oceans (although I don’t quite understand yet how to predict where it spawns if indeed one can, and please don’t tell me!), or an entirely new weapon that is far more effective than anything I’ve wielded before – or something minor, like a new crockpot recipe that doesn’t seem to be of much use but at least helps to complete and flesh out my list of recipes, or simply the ability to use a button input to spin carrots on the ground. Whether spinning carrots on the ground is just a silly little addition or has some deeper meaning – perhaps the Dread Rabbit God is summoned when enough carrots are spun?! (again, don’t tell me!) – I have no idea, but the game’s so far endless ability to always grow in size and always give me new things to find, is a real delight. Like so many other games I enjoy it’s a game that heavily rewards observation, experimentation, and deduction – and which is a real delight when played completely spoiler-free. Figuring out without any use of any hints how to fix the marble statues, or how the cave cycle works, or how to create a safe lureplant farm, or what to feed the antlion (though I still don’t know what the point is), or what recipes are the most effective for healing my sanity, or how to optimize the farm, have all been totally delightful. This is rapidly turning into honestly one of my favourite gaming experiences, and I’m very much looking forward to another year in the game.

Noita

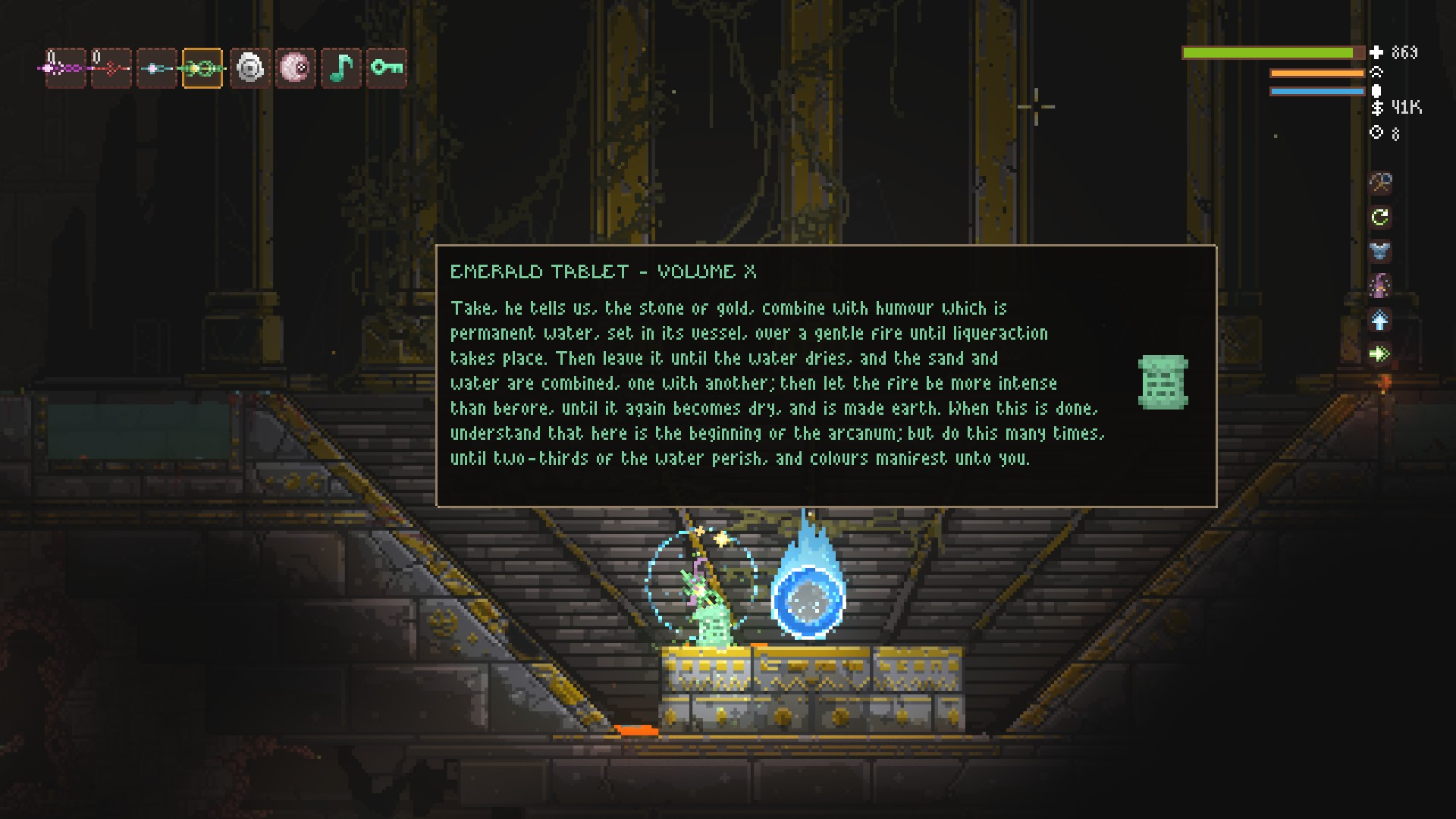

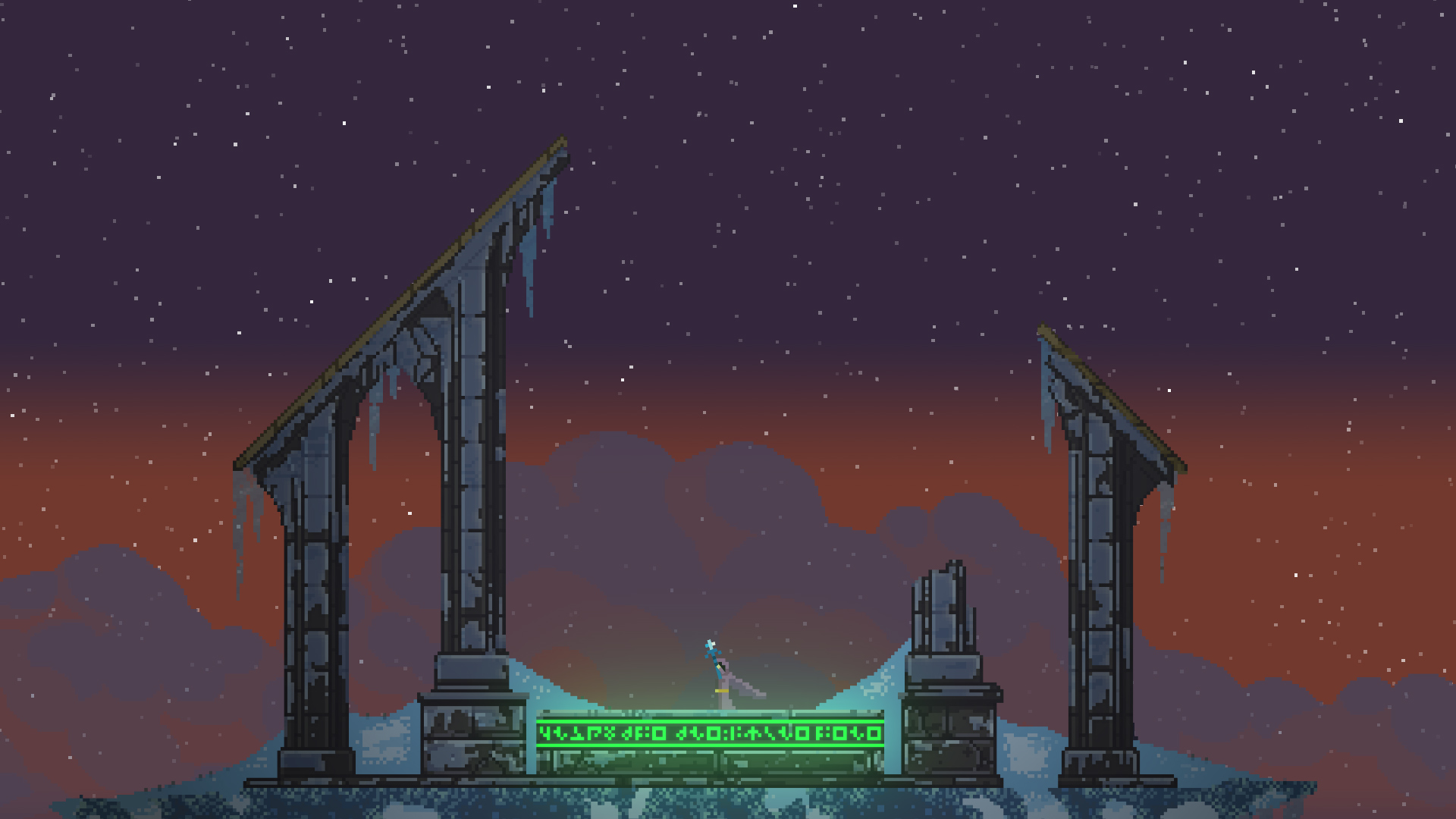

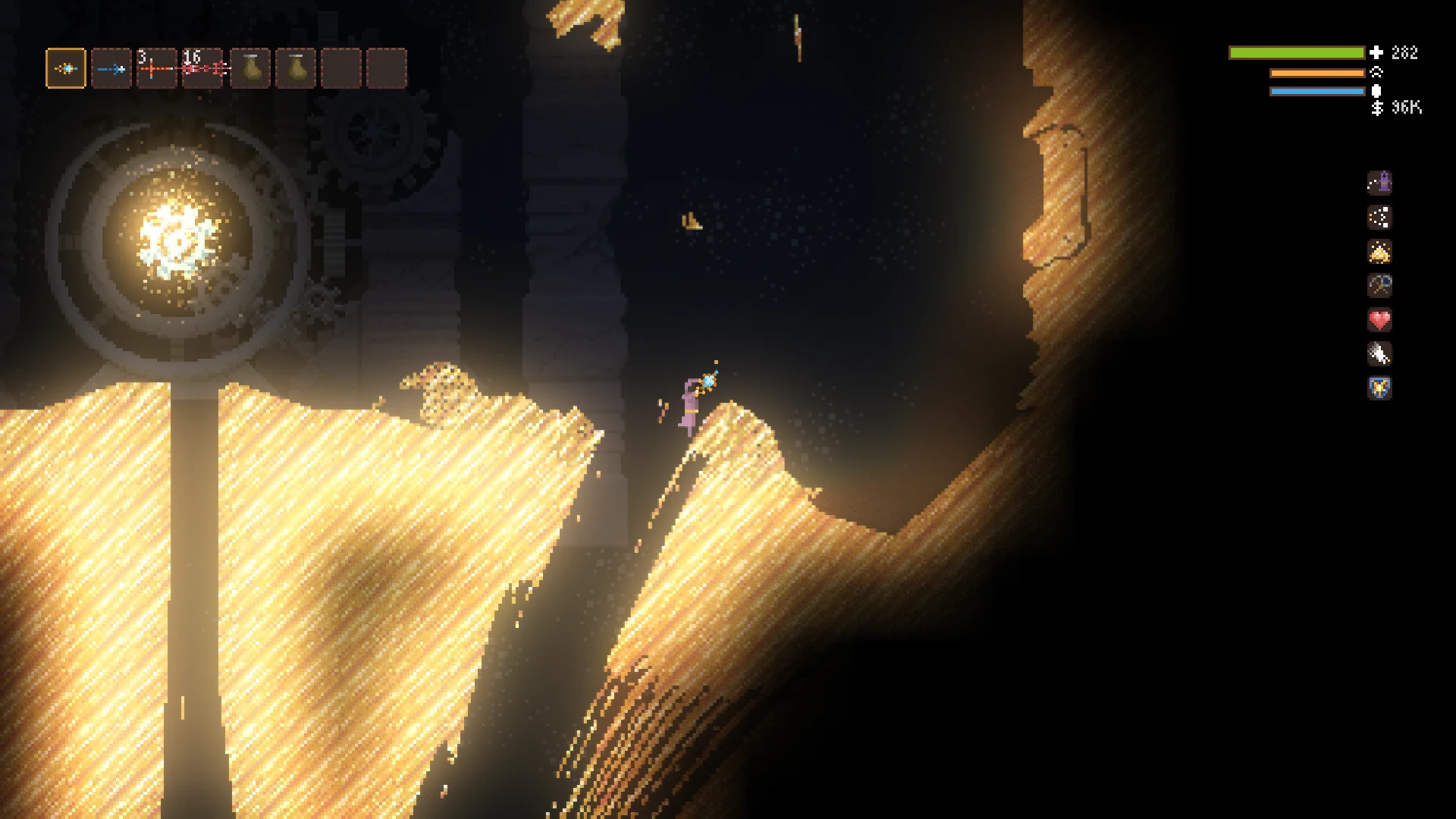

And now we come to Noita – described beautifully by one YouTube review as “a roguelike for the mentally deranged” – which is my favourite game of this year (although Don’t Starve Together has come very close). Noita is a platformer in which one controls a little witch / wizard character through a vast, baffling and extremely dangerous world, constructing magical wands with billions of possible spell combinations, pursuing understanding of astonishingly cryptic secrets, regularly dying and restarting in what is a pretty hard permadeath game, and most intriguingly, doing all of this within what is essentially a falling-sand-style simulation. I’m sure many readers of my generation or older will remember the early falling sand simulations, which – in the nineties – seemed to be remarkably complex physics simulations. There was something fascinating about creating simple but highly emergent systems where sand, water, salt, ice, and other materials of this sort all interacted in interesting ways. Noita’s entire world is of this nature, however, and watching the world’s interactions is one of the real joys – especially when one comes to figure out how they can be manipulated and used to ensure survival, defeat enemies, and so forth. This is one of the game’s many NetHack-like features, as the simulation level is sufficiently detailed that you really can kick over a barrel, and it explodes, and lights off a fire, and the fire spreads or doesn’t spread in different ways through different materials, and perhaps it then hits a pool of oil, and the pool of oil is instantly lit up, and it burns through a wooden strut, and so a chest on the wood falls and breaks open, and the thing in the chest spills out – and so on and so forth. NetHack players will be familiar with these long chains of logic that don’t actively involve the player’s agency, and Noita takes this to its extreme. The world is gloriously interactive and capable of so many novel interactions. Some of these can be fatal, of course, and the community naturally calls these “getting Noita’d”.

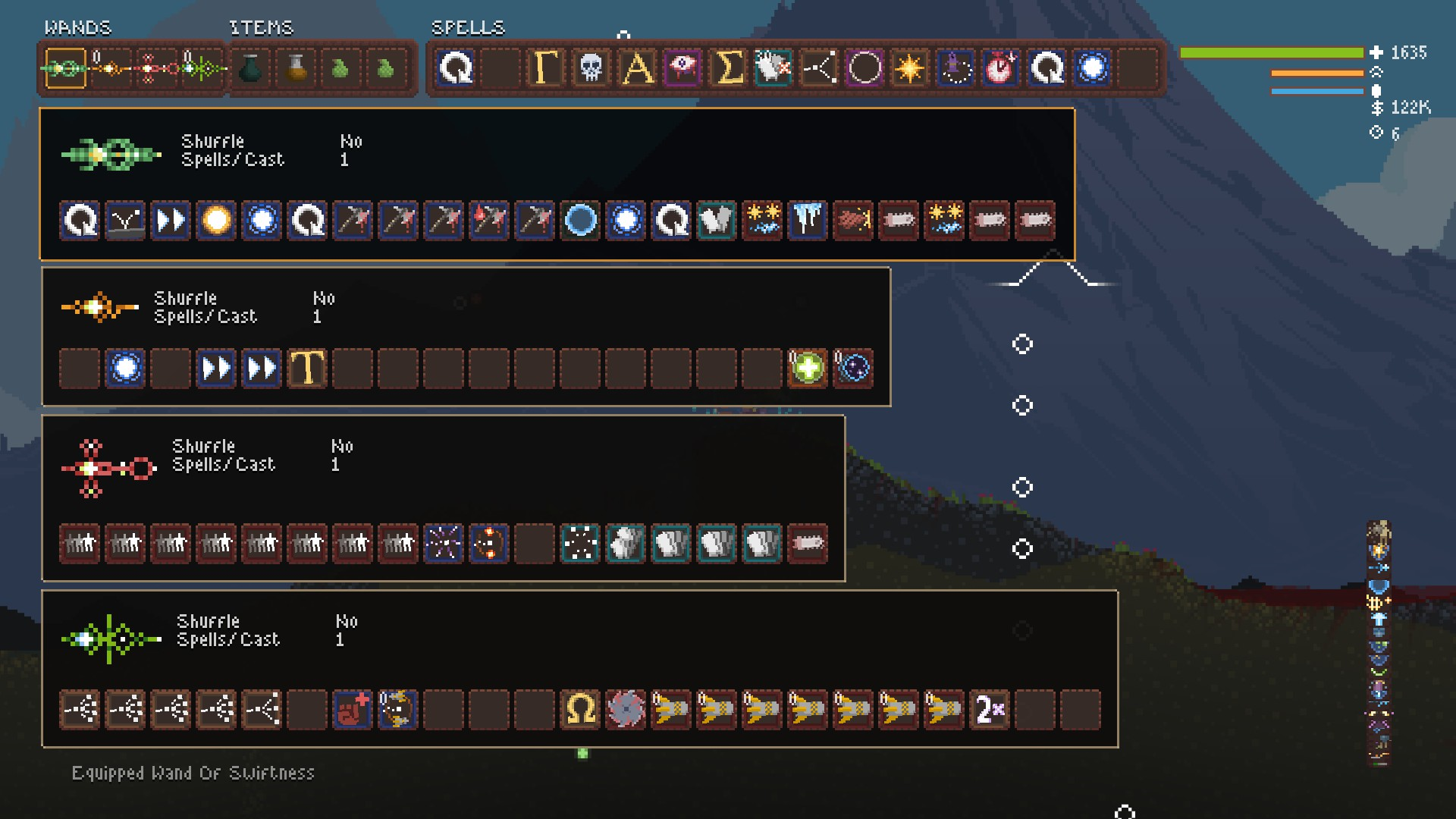

One of the most striking things in the game is its wand creation system, in which one combines spells and their various characteristics – speed of firing, the ability to change other spells, or imbue projectiles with certain properties, and so forth – in a manner that is very similar to programming. This takes a lot of understanding and getting used to, and the game doesn’t exactly help you figure out how to combine spells in a useful way, and much of the early difficulty in playing the game spoiler-free comes from the struggle of trying to create a wand that’s actually usable. Some of the more advanced spells even offer various options for recursion or simple logic, and the way that the spell modifiers combine with projectiles to offer such a towering variety of permutations is incredibly impressive. That said, one of the only issues in the game comes through here, however, which is that after mastering the wand creation system it’s very easy to always create something that’s very strong, as the sheer volume of the game world’s spells mean that there simply are some optimal combinations (freezing and digging, for example) that will always tear through most of what the game world has to offer. Some of the later and well-hidden bosses do attempt to force weapon variety on the player, and I appreciate that, though I think more in this area could absolutely have been done, especially when we compare to some other classic-style roguelikes which often require a range of tools to tackle enemies (Dungeon Crawl Stone Soup is sometimes quite strong in this regard, especially in the early game). Nevertheless, even if mastery of this system trivializes a key part of the game, the process of gaining that mastery, and enjoying and exploring what this system has to offer, is a really fascinating and rewarding part of the game. The first time you construct an actually good wand is a hugely exciting and empowering moment, and the basic idea of implementing this system is absolutely incredible. It feels like a magic system so many games have tried to create, but only Noita has really cracked that feeling of crafting your own spells.

I’m also a huge fan of the setting of Noita. It’s very loose, vague, and ambiguous, but essentially the setting is a mix of Finnish mythology and alchemist lore. Since reading Neal Stephenson’s Baroque Cycle I confess to having a real fascination with historical alchemy, as there’s something about an alternative, esoteric, mysterious and secretive attempt to divine the world’s secrets – in a manner wholly unlike actual science – which is really tremendously captivating. The game does a fantastic job of engaging with a lot of real-world alchemical lore and ideas, and the setting is overall really very unique and very mysterious. Within the unusual world it depicts, the game also gets a lot of credit for its enemy design, as you will encounter a tremendous number of different foes with a range of abilities, some of which might be more of less dangerous or deadly in various contexts, and the overall difficulty level of the game is high, with many enemies able to slay the unaware player without too much challenge. These also combine with the simulationist aspects of the game, so encountering an enemy which attacks with electricity might be especially deadly if you’re currently swimming around in water, for example. Again here we see this NetHack inspiration in really making the world a very important thing to be aware of and to always be thinking about, as so many attacks, weapons, magical powers and enemies are able to interact with the game world in such a range of ways that novel and unusual ways to perish are, as previously mentioned, always floating around the corner. In turn the sound design, although quite minimal, is great, and I really enjoy the music for some of the various in-game areas (especially the jungle), which does a lot to build up a sense of excitement the first time the player discovers them.

We also have to inevitably talk about how cryptic the game is. I’ve always been a huge fan of games that treat the player as if they actually possess a functioning brain and Noita falls comfortably into this category. Little is explained to the player in terms of the wand mechanics, the lore and setting, but also the player’s quests and objectives. There are many obscure and hidden quests and puzzles within the game world, a number of which require you to decipher cryptic clues and also gain a knowledge of the game world that is sufficient to put two and two together and figure out the solution. I don’t mind admitting, even as someone who loves cryptic puzzle games, that these are tough, and I think in some cases certainly competing with La-Mulana and its ilk for the degree of obscurity. The puzzles I was able to crack I felt very good about solving, but I don’t mind admitting that I needed a little nudge in the right direction, every now and then, for the trickier ones. All this contributes to the game’s overall feeling of mystery and strangeness, and the first time one discovers one has offended the gods – but without knowing how, nor what it means – is one of those unique mysterious gaming joys that are hard to repeat. I love all these sorts of things, and Noita has hidden and secret mechanics in spades.

Indeed, the game’s size really is extraordinary. I don’t just mean this in terms of the world – although it is, indeed, huge – but in terms of how much hidden stuff there is buried in the game beyond the explicit quests. I’ve always loved games that go out of their way to include secrets, easter eggs, and just little winks from the developer to the player savvy enough to find something obscure, and Noita is absolutely replete with these. On top of everything already listed, there’s also a range of mechanics around eating, drinking, vomiting, and a number of other related facets of this. None of these are ever explained to the player, and indeed remain completely optional. There’s also a mechanic by which ingesting a large amount of a particular fungus can cause the material properties of the entire world to shift, which is a wildly fascinating mechanic, and just such an extraordinary thing to bury deep in the game for the questing player to find. There’s also an entire alchemy system, by which potions and liquids and solids can be combined in various ways to yield various outcomes, some of which are fixed, and some of which are procedurally generated in each playthrough. All of this is extraordinary and I love it, but it does lead to my only real critique of the game – some of the most fascinating things which can happen are simply too rare. I have previously in some of my academic writing talked about the importance of having extremely unusual and interesting things in roguelikes happen only rarely, precisely because those striking things lend a distinctive veneer and noteworthiness to a particular playthrough. This is a design goal that I have followed extremely strongly in Ultima Ratio Regum – there are dozens and no doubt soon hundreds of things which are extremely rare, meaning that there are enough of them that something extremely rare will normally be seen by the player to make a playthrough feel special, but each individual one is rare enough that it’s going to be incredibly unlikely to stumble on the same one twice.

Noita has a wonderful selection of this stuff – including many things I don’t even have the space to cover here! – but some of it just shows up too rarely. A great example is the unique generated formulae on each playthrough for two particular resources, both of which massively change a playthrough, and neither of which the player is explicitly told. Steam tells me I have 100 hours in Noita and I have only seen these special formulae once, and that was in a run that died almost instantly and so I didn’t really get a full chance to experiment with hem and mess around. Having done some research online I believe 100 hours is actually pretty fast to see this happen, and I got lucky to spawn into a world where one of the formulae for the obscure substances was relatively simple (e.g. water, poison, and soil) rather than something astonishingly unlikely to ever randomly combine in the player’s line of sight (e.g. molten metal, vomit, and mysterious fungus). I think for such a potentially major gameplay mechanic, this might be just too rare? Rare mechanics and rare permutations are wonderful, but I think if most players will simply never encounter them – or even become aware of their possibility, their potentiality – then for me that’s probably a little much. That said though, I’m not wedded to this perspective, and I’d love to hear what others think about it. In such a detailed game, though, it does feel almost like a “waste” to have entire novel mechanics that can show up so rarely – mechanics that are well hidden but within the player’s control are fine, but mechanics that are well hidden and outside the player’s control… I’m not so sure.

I feel as if a lot of this review has been grumbling about minor points – yet this should not detract, I hope, from the praise I’m putting onto Noita. Indeed, many of these grumbles only arise from the game’s ambitions, the sheer amount of stuff shoved into this world, and the complexity, the riddles, and everything else the player might encounter. I haven’t even talked about how the main intended game route, i.e. the player’s path to a first win, is actually itself only the tiniest fraction of the entire game world (think DCSS and the extended endgame). Nor have I talked about all the bizarre mechanics involving generating parallel universes in the game world, creating wands with unique and baffling effects, breaking some of the game’s mechanics actually being an intended mechanic… and so much more, because there’s just so much. If a handful of things don’t land perfectly, that doesn’t bother me (I remember writing something similar about Rain World in an earlier entry) because they do land almost perfectly, but more importantly because everything here is so bold and wild and ambitious that a minor hiccup is really missing the point. There are places where Noita might be further tightened, but it’s already so far beyond what you could find in any other game, and the few issues only arise because the game is playing so far outside the norm. I would go so far as to say Noita is actually an inspiring game – not because of its specific material, but because it goes so hard at going so far outside the norm. As Ultima Ratio Regum increasingly procedurally generates riddles and graphics and all these things that essentially haven’t been seen before in roguelikes, games like Noita give me courage and confidence – striking out into that weird unknown terrain is worth doing, and even more pleasingly, it can even work out. Noita is a wildly fascinating masterwork, and I honestly couldn’t be more impressed. Give it a play, lose yourself in it, and you will not regret it.

In summary:

Thanks for reading, everyone! I hope you enjoyed these reviews; do let me know in the comments what you thought of these games, and anything you played this year, and stuff I might enjoy next year. The first game I’m moving onto in 2024 is going to be Returnal, which I’m really excited about, but beyond that I don’t have much else planned at the moment. Thank you all as ever for following along with the blog this year, I hope you all had a lovely break, and I’ll see you all in the coming year for more game dev updates and hopefully the release of 0.11!

A rather eclectic year, by all accounts! Congrats on the professional development, personal development, game development, and game playing development! What a lot of development you’ve experienced! How’s the health holding up? Didn’t notice any mention of it in the log, and was just wondering how you’re coming along. Ignore the question if you don’t want to get into it. 🙂

A quote from the HZD segment: ‘However, after getting around a quarter of the way through, I actually departed the game and haven’t yet returned.’

I did much the same. I played about a quarter upon release, which is when I bought it for PS4. Loved the visual style and the world was really intriguing and interesting. Then just outright abandoned it. I was going through a house move right after Rona and had little to do while my life was in boxes bar play my PS4 and starting working through my backlog. Dug that out and thought ‘sure, why not’ jumped straight back in to where I left it and without missing a beat thoroughly enjoyed myself so much I platinumed it. So if you’re wondering when a fantastic time to jump back on is: give it 4 years. I wasn’t let down.

Noita:

I followed it’s development fastidiously on Twitter way back when right up until it’s release. I then bought the game to show support and poured all of 8 hours into it. Never explored any of the West/East World stuff, never did any advanced mechanics, never did anything but beat the boss once.

Don’t get me wrong, I think the game is awesome and have recommended a fair few people try it (including my best mate, who has now put almost two hundred hours into it), but I think I loved the dev logs of it so much that it being finished almost didn’t live up to my own hype. Ruined my own love for the game, I feel.

Glad you played it, though. It seemed to have a very slight bit of love and hype on launch then really swiftly nobody was talking about it.

Thank you Conor! And you’re very kind to ask – I am pleased to say (touch wood) that things continue to be solidly on the “up”, though – like with anyone who has experienced serious ill health and then “recovered” – one is always waiting for the hammer to drop once again…

Your HZD experience is really interesting, and I love that I’m not the only person who dropped it at around the same time. Maybe I will indeed return to it at some point! I did find the world tremendously compelling, and my first encounter with one of the very very tall robots (can’t recall the name) was a wonderful moment. Noita: interesting, I was not aware of it until long after it had been released, and I was absolutely overwhelmed (in a good way) by how much depth and detail and complexity I found when I actually started playing it. Your experience is very interesting though, and it’s making me wonder whether I can think of any games that, as you say, didn’t meet the interest their devlogs generated in me. I’ll have to think on that…

Funny that I preferred La-Mulana 2 over the first game for the exact reasons you described. I loved both games, but some of the puzzles in the original game felt honestly too contrived for me – I much preferred the difficulty curve in the second game. I used guide for both games, but the sequel is one of those games that, if I was locked in a room with infinite food, no internet and only that one game to play, I could see myself beating it eventually. I’m not sure I could say the same for the first game.

Also, while I wouldn’t deny that the sequel was objectively easier puzzle-wise, I think you ought to take into account the fact that, having finished the first game, you had come to the sequel familiar with much of the game’s tricks; the fact that the sequel managed to bring to table enough challenge and novelty to keep things interesting throughout the entire game was, in my opinion, no less impressive than what the first game had achieved.

Hello Lee, thank you for the comment! I totally agree that the 2nd game has a milder difficulty curve; I was determined to solve it without a single hint and it still peeves me I took the hint for the neck-biter puzzle, though as you write, I think with infinite time I would have fully understood what the game was getting at in terms of a) each zone “being” an animal and b) the layout of the zone = the picture of the animal. Grrr. As for the first game, I think even with infinite time it would still have been damned hard. You’re also totally right, I did know the puzzle style, and I knew the level of absolutely comprehensive note-taking and observation that would be required of me! That absolutely helped.

I should upload my notes .png file at some point, simply for the comedy value – it is pure mayhem. Very much like that meme image from Always Sunny with the board and all the bits of red string pointing to various locations.

HNY Mark! I’ve very much enjoyed following your progress of URR and my excited for more in ’24. This is one of my favourite corners of the internet.

I’ve played a few off your list. Cannon Fodder is a cherished fave of mine, revealing my vintage! Sensible Software’s track record is phenomenal, not to mention diverse! I regard Wizball and Mega-Lo-Mania as exceptional designs. If Sensible Soccer was a modern game I’m sure it’d attract an e-sport crowd. It had the first 180 joystick roll I ever saw, a proper skill shot requiring time to master. It elevated the game past the casual and ate so many Tac-2 joysticks!

Noita, I die. A lot. In ways I suspect are primarily my fault. A punishing learning curve – not unlike my first love, Nethack, I suppose. But with Noita I’m yet to break through.

So OK – I’ll seek time to play a little more Noita in 2024! Good luck, health and spirits to you (and all readers) in 2024, no matter what your endeavours!

I think my 2024 darling was Dredge. A near perfectly executed risk/reward game loop of gathering resources, questing and upgrading your boat in a rustic archipelago. A pleasant living, if not for the Cthulhic beasts that just moved in, prone to hunt at night. It’s economical art design manages to still be very expressive (the water and ambient effects are brilliant) and the minigames are thematic and of perfect duration. It’s casual, you can’t really ‘lose’ but with so much here on-point, spending time in the world and solving the central mystery is very satisfying.

Thank you Shane, Happy New Year! And I really appreciate the kind words, thank you – I’m so glad you like the blog.

Totally agree re: Sensible Software, extremely strong stuff back in the day. Noita is really remarkably Nethack-esque in its design logics, at least in my view – it really goes heavy on the simulation aspects, on those cascades of events (I’m too heavy, so I trip, so I fall down stairs, so the item I’m carrying falls out of my hands…), and on the presence of really unusual but interesting edge-case strategies and things of this sort. Dredge: this is absolutely on my list, probably for 2024, though these things are always contingent on how I feel and whether I’m in the mood for X rather than Y in a given month. What I’ve heard sounds fantastic, though, and what you’ve written definitely adds to that. I am excited to check it out!

And thank you, you too!

I enjoyed reading these reviews. You’ve convinced me to give Into the Breach another try — I bounced off of it the first time around. And Noita looks awesome. I’m not sure how that one slipped by me.

Thanks crowbar! Yeah, I really love ITB. Noita is totally fantastic, and bizarre, and just so wildly bold and inventive. Let me know what you think of them both!