Welcome to 2022’s edition of “Some Games I Played in [Year] and What I Thought Of Them”! This year I’ve played relatively few games compared to recent years, but that’s in part because the ones I have played have been unusually time-consuming; also in part because of Covid becoming more manageable and therefore being able to get out of the house more (!); and in part because in the last few months I’ve been hard at work on Ultima Ratio Regum 0.10 which will be coming out in the near future, and also starting to write my second book (more on this in some later blog post).

So: let’s get started.

Blasphemous

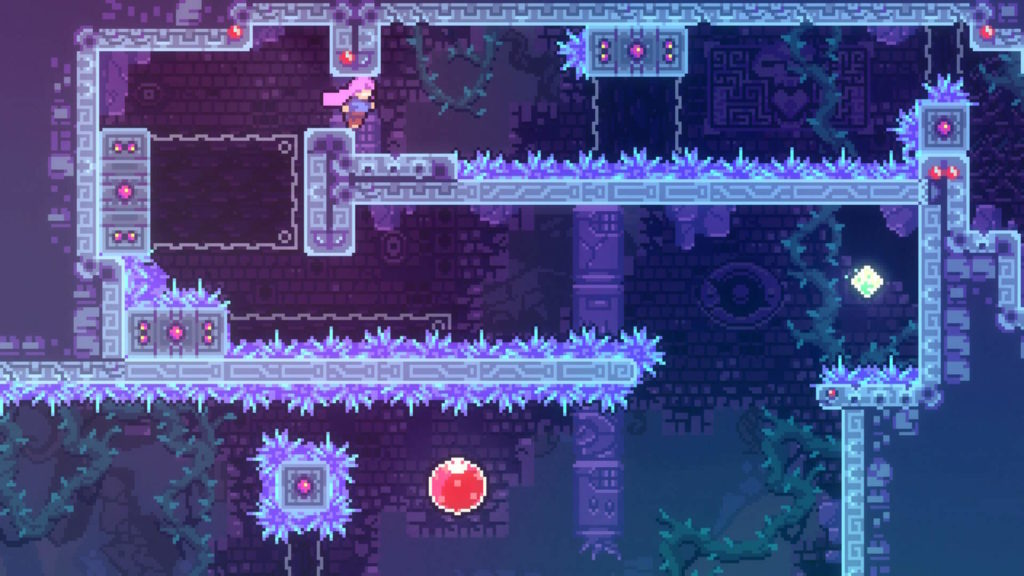

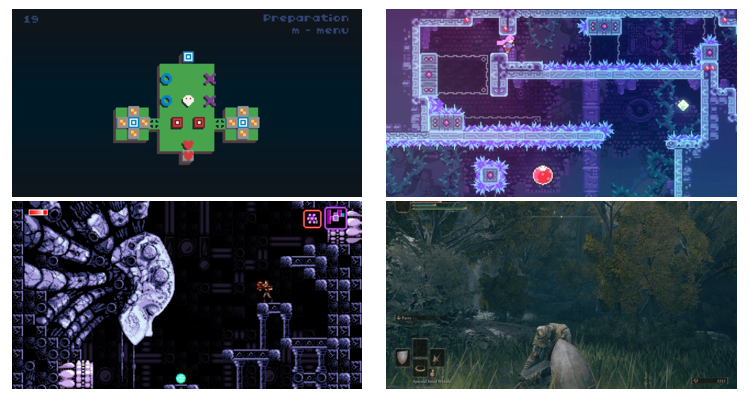

A strong and early contender for 2022’s game of the year is the answer to the question “What would happen if H P Lovecraft or Jeff Vandermeer wrote a novel set during the Spanish Inquisition?” – and that answer is Blasphemous. Blasphemous is a Metroidvania platformer – with some clearly Souls-esque elements and inspiration – set in a vast and bizarre medieval world which has been both afflicted and “blessed” by something called the Grievous Miracle, which essentially appears to be the action or the joke or the side effect or the manipulation of some sort of eldritch outer god(s). People reduced to mere strips of flesh are cursed by immortality; unfortunate individuals have other human beings growing inside of them; others are transformed into giant eggs and buried underground. The people of this land both struggle to understand the nature and purpose of the Miracle (if indeed it has one) and to live their lives in the context of this madness and mayhem, while also worshipping the Miracle in much the same way as one might worship a terrifying overlord; it is clearly in large part a worship of fear even if it regularly masquerades in the game as a worship of love. The Miracle has become so much a part of the life of these people and this place that strange cultures have sprung up worshipping particular facets of the larger picture. The people of the world themselves are baffled by the nature of this thing – and even after completing the hidden ending I remain somewhat unclear as to its nature and purpose, although a little more clarity has been obtained since via some lore discussions on Reddit threads I found. I have to say I thought this Lovecraftian-medieval setting was absolutely, absolutely stunning, and one of the most original I have ever found in a game.

The visuals are entirely beautiful, offering incredibly detailed and fluidly-rendered pixel art throughout. The enemies and the animations and the backgrounds are all gorgeous to look at and each area is very well-differentiated from all the other regions of the game. The level design is generally very strong – though a few of the hidden things are a little too well hidden, I think, and would probably really need a guide or just endless trial-and-error to ever really be found without assistance – and adheres to the usual Metroidvania style of doing things. I would have appreciated some slightly stronger fast-travel options as the game evolved, as these do exist but are somewhat limited, while a number of the hidden side quests – although intriguing and compelling in narrative terms – often just boiled down to a sequence of taking Item A to Place B, getting Item C, taking Item C to Place D, getting Item E, and so forth. Combat is very tight and very enjoyable, and there are a number of interesting upgrades in the game, some of which are really quite unusual. The music is lovely, with both the ambient tracks and the boss tracks doing everything they need to and giving a huge amount to the game’s setting. Although some of the backtracking could get a bit painful and I think the “true” ending might have been too well hidden, I still cannot quite get over how stunning – visuals, themes, writing, presentation – this world is, and what a complete joy it was to explore. The gameplay and level design are great and I particularly appreciated the small number of unique and obscure and somewhat La-Mulana-esque optional late-game puzzles, but the world is just spectacular. What a wonderful piece of work – utterly absorbing and compelling from start to finish.

Give Up The Ghost

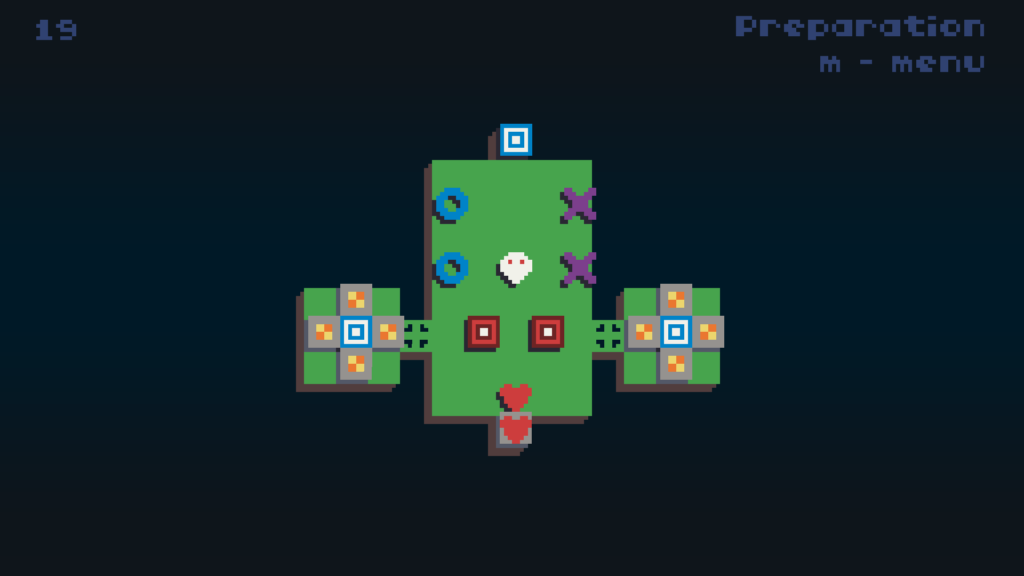

Back in my 2020 “Games I Played” post, keen readers will remember I discussed a wonderful and grotesquely difficult little puzzle game called SwapBot (and in doing so expressed my strongest possible appreciation for it). Well to my amazement and pleasure the dev of that game actually commented on the post and recommended me to their latest (and much larger) puzzle game, Give Up The Ghost, which I have been playing on and off throughout 2022. Whereas SwapBot is focused on a single core mechanic – any tile on the map can be swapped with any other – GUTG has a larger but far from overwhelming number of systems, some of which are very familiar from other broadly Sokoban-styled games but others are very unusual and distinctive, such as the ability to treat teleporters as objects rather than terrain and push them around the map, and the ability to move around an object that prevents other objects in its radius from being used or being activated. One has perhaps seen hints of some of these piece ideas in other games but these two in particular stand out to me as being extremely fresh, and the designer – unsurprisingly, given SwapBot – has been able to use these to create some truly mind-bending puzzles. The levels ramp up nicely in difficulty and both build on previous ideas and introduce new ones at a good pace, and it’s very satisfying finding uses and combinations of the in-game pieces that one hadn’t appreciated on previous levels. In turn, by taking pieces most gamers will be familiar with (e.g. teleporters) and doing strange new things with them (e.g. you can move the teleporters around), the game has a really fun interplay between what the player knows, what they think they know, and what they definitely don’t know, about the possibilities within the game space.

One of the things I particularly enjoyed here is how many levels went through a lovely pattern of seeming impossible, then you come up with an idea that gets you 25% of the way there but you encounter a new barrier you hadn’t anticipated; then another moment of inspiration gets you 50% there but introduces another issue; then another does the same for 75%; and then you finally find the way to sneak through all these obstacles and complete the stage, having somehow found your way around all these issues that only arose in the process of attempting the solve. The game’s designer actually notes that they specifically designed by looking for unusual edge cases in the interactions between the pieces they’d programmed in, and then making many of the levels specifically around those. This is – I think – a very unusual way to design puzzles and it really shows in these stages. I have to say, though, I think these stages I actually enjoyed less than some of the others, which felt to me like they were designed in other ways. The find-the-edge-cases levels sometimes felt like I was essentially doing a trial-and-error process until I found the edge case, or found something that hinted me towards the edge case, while other levels (again, I might be wrong about there being different design logics here) appeared to be much more closely designed around the gradual and iterative deduction of a solution. Nevertheless this is a great hard-as-nails little puzzle game, and I recommend it highly.

Celeste

Celeste is a gorgeous-looking game (with a fantastic musical accompaniment) about climbing a mountain and going on an inner voyage of self-discovery at the same time. I’d seen it around for a while before I gave it a shot, and I definitely enjoyed my time with it. The game handles wonderfully and ramps the difficulty at an appropriate pace; it’s vast in scope but very approachable, and has a very charming and whimsical sense of humour and presentation of its characters and places. One thing I really appreciated was how subtle – yet clear when one knows what to look for – the locations of some of the secrets are. With enough game-playing time under one’s belt it’s surprisingly easy to say “ah, that part of the level looks strange, there’s something there” or “why does this terrain extend all the way to the left when it doesn’t on any other stage?”. These are all subtle things but with the requisite game literacy I found it very satisfying to spot essentially all of these (I think?) on my first playthrough, including the crystal heart thingies, and these just gave a lovely sense of the designer talking to me, and me talking back, and having this very rewarding dialogue about how one spots strange-looking things in games even when they’ve been hidden. This was one of the real highlights to me and honestly the sense of mastery this generated was, for me, substantially higher than the mastery generated by the platforming itself (as I’ve seen platforming in a million other games, but the lovely ways a lot of things were hidden here were a much more understated thing).

However, I stopped playing around half-way through the “A” side and having done a little bit of the “B” side, and the better part of a year on I find that I haven’t gone back. It wasn’t because I wasn’t enjoying the gameplay, because I was, nor because I wasn’t enjoying the world and story and setting and themes, because I was, but it was for another reason – I feel like I’ve played it before. By this I don’t mean I’m having some unusually game-specific experience of déjà vu, and nor do I mean that in a past life I was definitely a Celeste player and the echoes of that existence are only now beginning to bubble up in my mind – rather, I am referring to Super Meat Boy. As far as I can think SMB was probably the first “indie” game I ever played (closely followed by Braid and World of Goo) and I really played a great deal of that game. Not just all the core content and all the more “advanced” or somewhat hidden core content – very demanding by standards of the time, but a little less so these days – but lots of the additional content as well, custom levels, all that sort of stuff, and I even did a little bit of SMB speedrunning as well. It wasn’t a game I mastered to the absolute highest level but I came pretty close, and its particular models of level design and gameplay and the feel of the character(s) are very strongly embedded in my mind. My primary issue with Celeste therefore is that the handling of the character, and the design of many of the levels and stages and the overall level design ethos – is just so similar to Super Meat Boy. As I progressed in Celeste I increasingly came to feel that – lovely and charming story and setting aside – I was just replaying a game I had already played. While I was keen to explore more into this setting the fact that the game is pretty demanding of time and effort, coupled with the fact that I have already mastered this particular specific sort of game in SMB, made me disinclined to continue on too far. This seems like a fantastic game, but I just needed a little more gameplay innovation to keep me hooked after a few dozen hours.

Halo Infinite

Now what a joy this has been! Every time Give Up The Ghost left me stumped, it was time to hop back into Halo multiplayer and decompress by stomping everyone I could find. I heard a lot of negative things about the singleplayer campaign – especially how it moved on from and largely ignored what I thought was a very novel and interesting conclusion to the Halo 5 campaign (which I watched on YouTube) and binned the “AI uprising” idea in favour of a more traditional battle against one of the Covenant’s races – so I’ve solely been playing the multiplayer. Yet even during my time with only the multiplayer I cannot say that the experience was anything close to perfect, unfortunately. The matchmaking often takes a bizarrely long time to come through and find me a game, and sometimes the menus would glitch out and prevent me from finding a match at all, often necessitating my restarting of the game. At other times it would find me a match and then I’d find myself in a vast map containing a single other human being, or sometimes it seemed to match me with some distant server whose ping was just far too low for anything approaching useful competitive play. In turn many of the in-game weapons were nicely balanced a couple felt entirely hopeless, leading to me joking that I would genuinely prefer to be unarmed than to have one or two of the in-game weapons (holding the weapon tricks you into thinking you might actually be able to fight, while being unarmed would at least be a state that far more accurately reflects your chances of survival). Similarly some of the vehicles are absolutely extraordinary in their power while others border on the unusable, and the game has an incredibly novel habit of sometimes randomly assigning kills to other people who didn’t actually have anything to do with the final blow (this is not just something I’ve been the victim of – I’ve also been the beneficiary!).

Yet despite all of these issues and teething troubles, I cannot deny that I’ve had a tremendous time with Halo Infinite this year. The core gameplay remains extremely compelling and with a very high skill ceiling, allowing both for teams as a whole to build up dominance in a given match and for individuals to shine and break through in moments of personal achievement or boldness. The maps are generally pretty strong and interesting and offer a lot of opportunities to play in a wildly different set of styles. It was actually a little tricky coming back to Halo after my last FPS being DOOM Eternal – whose pacing is somewhat different – but once I got into it the rediscovery of that subconscious rhythm and awareness of when one should be pushing forward, when one should be consolidating, when one should be defending, when one should be retreating, is all highly rewarding. When you get a really closely-matched objective game – similar to some of the apparently first-rate matches that this year’s World Cup has seen – there is such an excitement to be had when the score is equalised, or one team pulls ahead, or one team is almost about to score but both teams just pour into where the flag has been left or into the last contested territory to give absolutely everything they have. In turn, given that I essentially did nothing else during my teenagerhood except train with the Halo 2 Battle Rifle for the better part of five years, it is very pleasing to see how well those skills continue to translate into a contemporary Halo game (and a contemporary player base as well). I have neither the time nor the interest in pushing the competitive modes in the game as far as I could get them, but in a time when my life is pretty much exclusively singleplayer games, I really relished this return to competitive gaming and a reminder of why I spent so much of my teenage years playing these games, going to LAN parties, and all the rest of it.

Axiom Verge

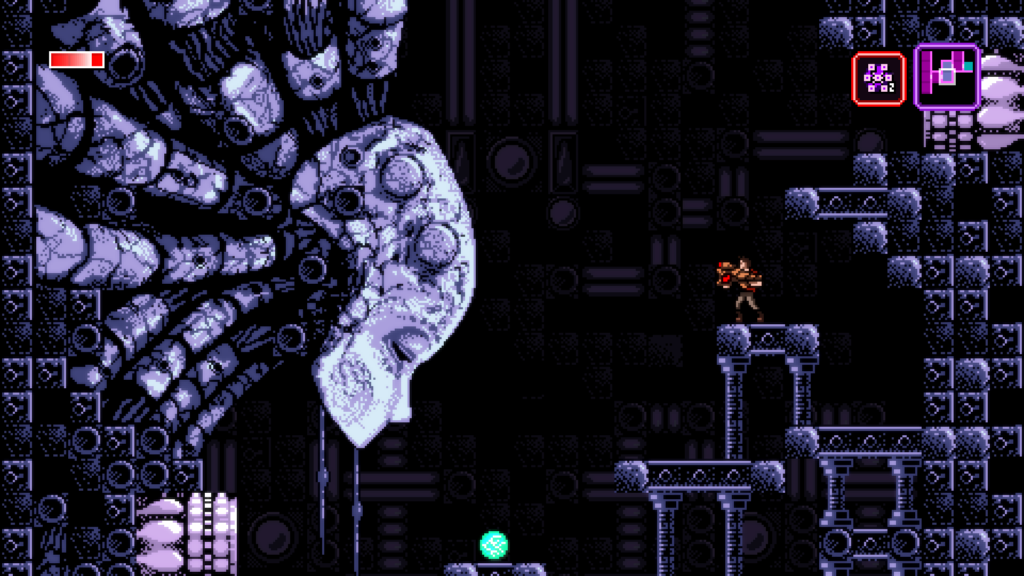

Axiom Verge had always stuck out to me with how striking its pixel art seemed to be – particularly some of the larger creatures / structures / characters (as in the above example). Late last year I decided it was finally time to give it a look and what I found was, honestly, really very strange. The graphics were beautiful, the audio fantastic, and some of the in-game items and weapons were genuinely hugely original and fresh, and the game did a lot of clever stuff. On the other hand, the moment-to-moment platforming / exploration, and how extremely Metroid-esque it is in many ways, left me very cold. I found it very difficult to settle into any kind of rhythm and really just felt as if a lot of the game was filler to get some from one beautiful pixel art boss or weird and original weapon to the next. There are so many fascinating ways to deal with enemies and yet dealing with enemies is rarely interesting because few pose compelling or novel challenges to the player and serve little function except to get in your way, briefly, before being swatted aside. Several of the mechanics could have made for entire games by themselves yet here they are thrown at you in an overdose of interesting things, but which have relatively little interesting to do with them precisely because of the repetitive level design and the slow or trivial enemies. Comparing the game to, say, Hollow Knight or La-Mulana, really highlights how bland and similar all its areas are, when placed in contrast with the wildly artistically distinct areas in those sorts of games.

In a way Axiom Verge reminds me of a magic trick whose vision and creativity is astonishing, yet is presented to the audience with very little showmanship. There’s so much here to explore, and yet the blandness of the game’s areas mean the game does surprisingly little to grab you, draw you in, and keep you in this world while it shows off all its cleverness. It does itself a disservice. Most of the game is astonishingly novel and inventive with weapons and mechanics and tricks that are genuinely incredibly original and interesting and fascinatingly weird (the “Address Disruptor” stands out, though the “Drone” is also a total joy to play with, and the “Pathogen” section of the game is just fascinating), yet the sterility and blandness of most of the game’s regions (despite the exemplary pixel art) just don’t do credit to how much potential the work really had. The level design doesn’t change at all from area to area, and the areas rarely have distinct features. Contrast this with many contemporary Metroidvania games – or even early Sonic the Hedgehog games for that matter, where each area always has a set of unique features – and the different shows up really very starkly. An embarrassment of creativity and riches that is tragically unpolished and often surprisingly bland, Axiom Verge was a peculiar game where the creator had designed so many interesting and novel concepts yet never really gave you a huge amount to do with them, creating a highly intriguing yet uniquely frustrating experience. Rarely has something so beautiful been so sterile, nor something with such originality somehow also been so repetitive. Because I rate originality in games so highly I still enjoyed my time with Axiom Verge, but all the moments of fascinating and intriguing weirdness it offered were, sadly, consistently undermined by other aspects of its design.

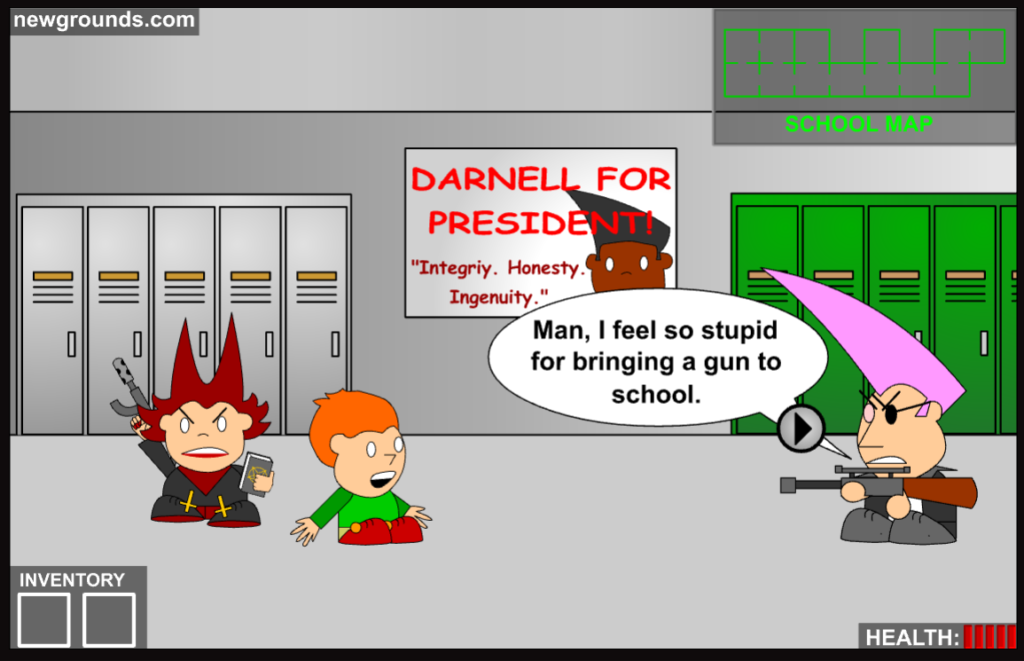

Pico’s School: Love Conquers All

This game is no more than five or ten minutes long and yet it is – no joke – a strong competitor for my game of the year. The first time I played it I actually clapped my hands together with glee and amazement and delight when the end credits rolled (how often does someone do that?!) and actually had to sit back with it for the better part of half an hour digesting it, reading others’ commentary on it, and thinking about what a clever, charming, and heartfelt thing I’d just played. For those who have never come across the original “Pico’s School”, this was a very influential Flash game released on Newgrounds back in 1999. It really pushed what was technically possible in Flash games by having things like an inventory (!!) and was also very bold and in-your-face – like a lot of “underground” internet media of the time – by telling a story about a school shooting, countered by the player character’s own competence with an automatic weapon, and culminating in the big reveal of an impending alien invasion of the planet. This might sound rather peculiar but I promise it makes a lot more sense when presented through the game itself. The game was hugely impactful for me, and it was striking how different it therefore was from pretty much other game I’d played until that point (although I suppose, in 1999, the most subversive / “edgy” games I’d previously played were GTA 1 and Duke Nukem?).

In this sequel / remake / alternative universe version, however, the school shooting is averted through Pico’s (your) ability to talk to each of the attackers and to understand something about them – about their alienation, about their home lives, about their hopelessness, about their lack of agency and their poor decision-making and their psychological desires to exclude and separate themselves from others as a form of subconscious defence. It exchanges the teenage or early post-teenage edginess associated inevitably with the topic of a school shooting for an incredibly sensitive and mature understanding of the subject area, yet one that by presenting it within the same art style and context of the original holds a striking amount of narrative power. What really stands out to me is how, having experienced the game in its first iteration over two decades ago, I was able to truly enjoy and relate to what a clever, self-referential, thoughtful, and like I say actually surprisingly touching piece of work this is, precisely because the original has sat with me for around two thirds of my entire lifetime. The sense of time between the original version and this had somehow given the original an astonishing degree of weight, at least in my mind. It was as if the fictional events of the first were actually historical events, were things that had taken place (even if only digitally) at a particular time and in a particular context, and this was an irreversible and hard-coded piece of (gaming) history.

By releasing this alternative version, Tom Fulp has offered a tremendous clever and tremendous ethically aware commentary on the original piece. It’s a game about an artist reflecting on their earliest work – a work that was hugely influential and important, yet also full of post-teen angst, as I suspect Fulp himself would admit – and engaging with the passage of time and their own development as a person and a game maker. The game isn’t in any way asking us to extend our sympathy to a school shooter, but it is acknowledging the fundamental truth that nobody who is happy with their lives, who has safe and loving homes, has ever decided it was a great idea to destroy their lives and the lives of others in such an event. What PS:LCA is saying is that none of these events are inevitable and there are always other paths; as Marx said, we might not choose which options are available to us, but we do still choose which of those available options we take; and there are always ways to move from the darkness into the light, no matter how impossible it seems. What a fantastic and lovely piece of work.

Now, please do remind me about this in a decade, everyone, when I’ll have to come back and make some clever self-referential parody of URR.

Don’t Starve Together

I’m really not a survival game player. I often cannot help but find survival games to be repetitive, tedious, shallow, often a little mindless in some of the activities they expect you to do in order to not die, and it doesn’t exactly stand out to me as a genre that displays any kind of innovation. My views on survival games have probably – unfairly – been further tainted by the immense volumes of survival game trash one can find on Steam constructed from generic garbage on the Unity asset store, and so the genre has certainly acquired in my own mind a sense of mindlessness and amateurishness which is probably unmatched by any other genre. Some kind of survival elements that are properly integrated into another kind of game – like food clocks or equivalents in roguelikes, of course! – are entirely defensible, but purely survival games have rarely been able to get any interest. Don’t Starve, however, I have found I absolutely loved! I had long been tempted into the game by a few people on Twitter who had recommended it to me and by its gorgeous art style, and I’m really glad I finally gave it some time. I think on my first playthrough (I’m entirely spoiler-free and continuing in that way) I survived a towering total of five days; this later ramped up to a number of playthroughs at around thirty days before dying to the (infamous?) Deerclops enemy every time; then after finding how to deal with but not kill it I then consistently reached fifty to sixty days, before burning to death in the summer. After figuring that out, however, I’m pleased to say I’ve now reached around day 500 with no turning back.

In games like Into the Breach (and some more classic roguelikes too) one often gets the feeling that the particular thing the game has dealt you simply cannot be solved perfectly… but then, after some study, a perfect solution does present itself that doesn’t consume any health, or any finite items, or whatever it might be for the game in question. When learning the game Don’t Starve does this really nicely where the relentless march of the seasons, invasions by hostile creatures and all kinds of other stuff keeps one continually thinking there’s just too much to do, but with a lot of effort and planning you can just about keep ahead of the march of time and requirements. In turn, even when you’ve reached the point of becoming able to keep yourself alive indefinitely, there are always more and new challenges you can go and face which can potentially interact in tricky ways with older challenges you felt you’d mastered, and the game retains the ability to surprise you at any moment. The first time that I had grown so much food so successfully that a secret boss actually spawned specifically in response to my agricultural successes was quite a shock, but a delightful one. There’s also something roguelike-y about it – or in fact, to be more specific, something especially Nethack-y or Dwarf-Fortress-y about it – in how many systems the game has that interact with each other in all of these interesting ways and can generate this unknown (and sometimes amusingly calamitous!) outcomes. The inclusion of permadeath meanwhile, and no ability to save or backup or reload or whatever, combined with the other elements, really sold me on this. Finally a survival game where it is actually not taken for granted that I will survive! With permadeath always looming the game offers you a real sense of pride when you master survival or overcome a boss or optional challenge or puzzle that had previously stumped you, and a real sense of intensity and drama when things start going poorly. I remain unspoiled but keep discovering new things, and I’m looking forward to learning just how ludicrously far (I suspect) this game might go. I really love this game and is probably the runner-up for my game of the year – it’s huge, challenging, beautiful to look at, chaotic and unpredictable while also complex and deep, and I’ve had a tremendous time with it.

Elden Ring

Urgh.

To start with here, let’s take a moment to look back in time a bit. Dark Souls 1 was released in 2011, and if memory serves me correctly I played it in 2012. At this point I was living in a shared student house with two others – I was a year into my PhD and my flatmates were finishing off MA and PhD degrees themselves. We were all of us avid gamers, and although I was probably the one who spent the most time on games at that point, all three of us were definitely not gaming to anything like the extent we had been in our youth. Although I cannot speak for my flatmates I had – looking back – begun to feel almost automatic in my gaming, and although I was still enjoying playing good digital games, I couldn’t honestly say that anything recently had challenged me or surprised me or startled me out of my comfort zone or really helped me rethink the medium. Dark Souls entirely changed that, as did most of the sequels and related games released by the company, startling me into new ideas about the presentation of games, the play of games, and the deep mysteries and challenges that games can provide. Along with Chip’s Challenge, Command & Conquer and NetHack, Dark Souls is one of the four most “important” games I’ve ever played and that have left the longest-lasting effects on me. The series has been a strong inspiration (though I admit this might not be obvious from the outside!) on my own game development work and my own thinking about games more broadly. I’ve replayed Dark Souls 1 & 3, Bloodborne, and Sekiro more times than I can count, even to the point of doing challenge runs, and have delved massively into the weird, baffling, and totally singular “lore” of these games. Years ago I even wrote a few (quite mediocre, let’s be honest) blog posts about these games on my old website, and although I’m not particularly impressed by those posts coming back and they really show some of my earlier (lack of) development as a games writer, they sprung from just an earnest and genuine desire to somehow contribute to the conversation around these incredible games.

I was anxious when Elden Ring was announced and described. I didn’t see how an open world game could possibly capture what is so magical about this series – but I put those fears to one side, expressed confidence in Miyazaki and the team, and… unfortunately, I was proven entirely right. Elden Ring was a crushing disappointment for me. I completed it all solo, but I cannot say that I really enjoyed more than a third of it, but I kept going thinking surely there must be more or this cannot be it or there must be some amazing fascinating area around the corner… but these rarely came true. Within hours of playing I was genuinely staring, mouth open, aghast, at what was playing out on screen – a big, bland, empty area, full of nothingness, which appeared to lead onto other big, bland, empty areas of nothingness. Every now and then I’d discover an area that was somewhat reminiscent of the classics – rarely to the same standard, though the “Leyndell” area was excellent – before being pushed back into another open world filled with absolutely nothing and endless journeys on your horse. Even worse were the repeated mini-dungeons which I genuinely, to this day, cannot believe made it into a From Software game; that kind of tedious rubbish is for Skyrim only (or so I thought). The endless reuse of enemies was also even more ridiculous, with even the most “unique” bosses later turning up as just generic foes, and all of this happened to a vastly greater extent than in any previous game. I found it hard to care about the fights and the encounters and the areas, and although I did solo Malenia, I have to admit that towards the end I largely started using the “Mimic Tear” item on every fight; not to overcome any difficulty but because I did not care enough any more to play the game how I normally play these games, and I just wanted it to end. End it did – not with a bang but with a whimper – and I found myself wondering why I had spent 90 hours on this vast expanse of nothingness and repetition. What is even more bizarre to me is that so many reviewers and players call this FS’s masterpiece, which is akin to saying Death Proof is Quentin Tarantino’s finest work or The Naïve and Sentimental Lover is where John Le Carré really shines. I’ve really been feeling like I’m living in a parallel universe when it comes to Elden Ring for the last few months and I just do not get it – a deeply unique and iconoclastic game creator / company have shifted themselves massively towards the mainstream, towards what everyone else does, away from the uniquess and staggering and baffling works they once made… and this is an improvement?!

Now, there were quite a few moments of From Software brilliance here, but it was all mired in a dreadful swamp of open-world tedium and blandness, Skyrim-style repeated dungeons, and thematic and story elements lifted heavily from Dark Souls (and to a lesser extent Bloodborne) with relatively little here that was actually new. I cannot quite decide whether the time I spent with the game was worth it for those strong moments, or not worth it because of all the weak moments, and it’s… it’s right on the border for me. What I know for sure though is that if any DLC comes out, I will not even look at it unless I confirm first that it’s all classic FS dungeon design, instead of more even more of this bland, directionless, wandering, rubbish. What a terrible disappointment this game was for me – and since it has done so financially well I worry the halcyon era of FS games may be over. If their next game is another Elden Ring, as unthinkable as such a statement would have seemed even just a year or two ago coming off the brilliance of Sekiro, I actually might not buy it.

What a let down.

Grand Theft Auto

For some reason I found myself returning to Grand Theft Auto 1 this year. I cannot quite explain why except that I was fascinated to see how the game now plays and how it holds up, and I confess that I found something really quite striking and singular, if sometimes really just a bit too over-the-top. What really stands out about the original GTA is how there is a striking anarchy and craziness to the game and its missions that even in the initial 3D games was lost. One mission, for example, has you seize a District Attorney from a hospital, taking advantage of this opportunity because he’s in there for “an ingrown toenail”, which is apparently enough to get you to hospital and at the mercy of the local criminal gangs. Another mission has you destroy a car moving through the city and kill its driver without much explanation, after which the person who gave you the mission shouts “Take that, mom! That’ll teach her to bug me for the rent”. A third mission gets you to recover some “home videos” starring a local gang boss, but then your immediate superior jokingly tells you “hey, maybe we can watch them before we give them back!”. A fourth has you obeying the orders of some kind of insane millenarian cult leader determined to show the world they are the “one true God!” by enlisting your assistance in blowing up a train and all the passengers on board. In another section after saving a gangster’s wife the gangster bemoans the fact that now she’s back she expects money from him for plastic surgery, suggesting that the gangster in hindsight now wishes you’d just left her at the mercy of her kidnappers. Numerous other missions make some astonishingly raunchy jokes that I’m actually not going to repeat here (given that I like to keep this blog largely PG). It’s like all the criminals in these cities are edgy teenagers and there’s a real rawness to these missions and to the script, often having your player character mow people down because they bought a car in the wrong colour or some gang lord is simply in a bad mood. Often it feels like Beavis and Butt-head are the ones giving you your objectives, constantly upping the stakes on the crassness, strangeness, or sheer perversity of the missions given. The GTA games have never gone for heavy realism but the later games at least paid lip-service to the idea that they take place in a real location with real humans, especially as they moved towards more “simulation”-heavy game design and world design; this is certainly not the case in GTA 1, where everyone is a berserk lunatic and massacres are gleefully ordered at the drop of a hat.

The game’s design weaknesses also really stood out to me all the stronger now two decades on from my first playthroughs. The most obvious is the lack of differentiation between the areas of the game, made all the more frustrating by how little effort would actually have been required to change the look or colours of the roads in each district, for example, or the style or shading of the pavements. I speak from game dev experience here; once you’ve implemented X it’s very easy to implement X(1) and X(2) and X(3) in order to vary X, but unfortunately GTA 1 never does that. The three cities you spend time in are, overall, distinct, but areas within a given city are almost indistinguishable unless there’s something absolutely unmissable (a large park, it’s next to a canal, etc) to set them apart. Over time you do begin to get a very loose sense of where the most important areas of each city are – which is to say rivers and bridges, as those are important for your navigation of each location – but so much more could have been done here with really very little effort. Similarly, although the intensity of the police attention does ramp up the higher one’s “wanted level” becomes, it never goes beyond just sending more and more police cars at you and sometimes setting up police barricades. It would again have been pretty trivial to implement some of the additional levels of attention – from SWAT teams, the FBI, and eventually even the army – seen in later games when your criminal exploits reach the most ridiculous levels of destructive impact. “More police cars” is fine, but more variation in these responses to your actions would have been a great addition. The variation in the missions could also have been improved, as while the narrative justifications remain as bonkers as ever throughout the game, there are few missions that aren’t variations on “go to X”, “take car X to Y”, “kill person X”, “kill group of people at X”. These do come to vary a little more as the game progresses, but not fast enough, and not to a large enough extent.

This was a fascinating game to revisit – and I had truly forgotten how astonishingly raw and in-your-face the writing is – and although I really enjoyed my time playing it again, a lot of its design does feel quite outdated now (unlike some older games)… yet there is a hyperactivity, a dynamism, an intensity here that actually isn’t necessarily found in quite the same way in the later, and far more successful, installments in the franchise.

Other Puzzlescript Games

(Clockwise from top left)

White Pillars

This game was great. It’s only a handful of levels but the basic idea is that what you have to do on each level changes – though it always involves some variation on pushing the white pillars or positioning them in certain ways or moving them in certain manners – and you have to figure out from a handful of contextual or subtle clues what you have to do in each level. The difficulty ramps up nicely (though not I think in a linear manner as I would certainly order the levels differently) and there’s a real pleasure in being able to decipher or decode what the game is asking of you on each level despite the stark aesthetics and the absence of any kind of helpful text or instructions. I do think the levels could have a different sequence and I think the game could be a little longer with more varieties as well, but what’s here is short but novel and very satisfying, and it’s nice to see a game completely built around this sort of “work out the game mechanics” idea.

I Wanna Move Once More

This game’s core mechanic is quite a novel one that I don’t think I’ve really seen in Sokoban-style games before; the previous block you moved will move again when you move the next block. It sounds like a relatively simple system but in such tight and enclosed spaces of the sort the game offers you, and often with substantial numbers of pieces that need to be maneuvered into position, this quickly makes for quite a challenge. One is always of course thinking multiple steps ahead in most Sokoban-style games, but having to think multiple steps forward not just for an individual piece but for multiple pieces, and how the movement of those multiple pieces will change the possibilities of the map in the future, is very nicely tricky. I think what makes it even harder is how used to being the only source of agency in these styles of games a player can become, and discovering that the pieces also possess some agency on your own taxes the brain in some surprisingly new ways. Really good stuff.

Sliding Ground

This game added an extra layer on top of moving around blocks to have you also moving around the floors that you move blocks around on top of. The little green cross pieces I’ve shown in this screenshot are floor tiles that you can walk on like normal floor tiles, but which also move around – and potentially combine with others into interestingly-shaped pieces – when you’re on them and trying to walk. This added an intriguing extra dimension where you are also changing the layout of the map and the terrain that blocks can be moved onto, as well as having to think about what geometric combinations of floor pieces can be constructed or should be constructed to get through the level. The later stages in particular are surprisingly tricky and really needed the player to think outside the box – not just about combining the sliding floors but also not combining the sliding floors, or sometimes not combining them until a given stage of the level. Very interesting stuff, and with a lot of those really compelling levels that really do look impossible until that moment of inspiration strikes.

Sokoban in Sokoland

This was a really interesting one, offering a long sequence of levels where the precise game mechanics being used on each stage vary. The initial mechanics begin pretty simple but then ramp up to increasingly puzzling or strange mechanics. There is some commonality and overlap of course here with White Pillars but this game offers far more levels, although the focus here is less on “what is the mechanic in this level?” and more on “how do I use this new mechanic to solve the stage?”. These are some very novel ideas packed into here and although I think a handful of the levels have relatively “loose” mechanics which aren’t always that interesting and lend themselves to huge numbers of potential solutions, most of the stages are much more tightly focused. A really pleasing high-speed dash across a range of ideas and a range of different thought processes for the player to get to grips with.

La-Mulana

And now we come to my 2022 game of the year. La-Mulana has always been one of those games one hears whispered about in discussions of “the hardest games ever”. I’ve actually never been one to pursue many of the games on those lists – so-called “masocore” titles like I Wanna Be The Boshy and its ilk don’t really hold a great deal of interest for me because of their arbitrariness and strong emphasis on rote learning – and I’ve always looked at such lists a little askance because of the exclusivity and elitism they can (sometimes) imply or reinforce. Yet La-Mulana has long intrigued me; so many contemporary and critically-acclaimed puzzle games (e.g. The Witness, Inside, Baba Is You) tend to leave me cold and not quite hit what I’m personally looking for in a puzzle game – and it is perhaps therefore worth noting that none of those games tend to make it onto these ultra-hard-game lists. The combination of La-Mulana’s presence on these lists, combined with the fact that it is primarily a puzzle game, was enough to pique my interest and give me hope that this might be the sort of long, complex, winding, overgrown, baffling, awkward, labyrinthine, sprawling puzzle game I was looking for – and I was not disappointed!

La-Mulana sees you exploring a vast set of ancient ruins where progression is primarily tied to the solving of a massive number of puzzles, some of which are merely mildly cryptic and some of which are cryptic enough to compete with a classical Neopets plot puzzle. The platforming is difficult and unyielding enough but the real challenge lies in these mysteries, whose clues are scattered across hundreds upon hundreds of stone tablets in the game world, and the puzzle or puzzles each tablet hints at are generally not found in proximity to the tablet itself. The player is therefore tasked with keeping track of all these clues and trying hard to connect them to what they’re seeing externally in the in-game world. In turn what can and cannot even be interacted with in each room is rarely clear, and the distinction between background visual elements and vital puzzle components is equally obscured. All of this forces the player to take extensive notes, to have an excellent memory, and to work extremely hard to find the possible connections and interpretations required to advance the game. Much like in The Outer Wilds which was my game of the year last year, all puzzles here are “qualitative” in the sense they do not belong to a system or category of puzzle, but are (pretty much) all unique, and this uniqueness simultaneously makes them extremely hard to solve and extremely gratifying when one does. There is no previous specific experience one can use to solve a puzzle, but rather only a gradual appreciation of how the designer’s think will help you out.

There are roughly twenty areas in the La-Mulana game world, each of which has twenty rooms so that’s four hundred total. Most rooms have at least one puzzle in them, and a few have more or contribute to multi-room puzzles, so let’s say that there might be in total three hundred distinct puzzles. If we work on that estimate of 300 I can truthfully say I solved 297 of the puzzles myself; I believe it was only 3 that stumped me. Given the nature of the game I don’t mind admitting I’m pretty darn proud of that total, and having done a lot of searching online it’s clear that although a tiny handful of players have completed with the game without any support – this video is a fantastic example of someone who somehow achieved this feat, although understandably with around double the playtime I racked up – in my own playthrough I managed a high level of completion. As I progressed I became quite quickly determined not to use a guide or even a hint unless I had just been banging my head against a wall for too long – this always meant at least multiple hours without even the slightest hint of progress, or the slightest hint or where I might progress. I tried my absolute utmost never to check a hint, and in fact, in hindsight I really do wish I hadn’t taken a single hint. The satisfaction one feels when solving a tough puzzle is not just the satisfaction in solving a tough puzzle, but something that feels like a conversation you’re having with the designer – they scattered the loosest and vaguest of clues in their ridiculous game world and trusted you to be able to piece together these disparate elements into something logical. However, the question of “where?” rather than “what?” was, I think, the game’s only possible flaw and my one complaint – the challenge (especially in the mid to late game when almost the entire map had been opened but one still had dozens and dozens of unused clues) but sometimes less in knowing how to solve a puzzle and far more in knowing where to find an unsolved puzzle.

This was in fact my primary source of (un-fun) frustration in La-Mulana. I found myself often having clues I could use and maybe even some idea of what the clue might point to, but no idea where to actually use it; and by the same token I had plenty of in-game areas where it looked like there was a puzzle to be solved, but no idea whether or not I currently possessed the information required to crack it. Now, people who have defended this inability to know where to go have suggested that this is an intentional design choice – by getting the player going over and over many times the same ground, they will notice things and note things and pay attention to things that they might otherwise miss, and this will be important in later puzzles. This is a very interesting design justification and I’m honestly not sure how I feel about it – I did find my time going back-and-forth to just find something frustrating, yet one could also say that was my failure to take sufficient notes first time around coming back to haunt me. I do wonder whether the game might include some kind of system that tracks precisely what items you have and what riddles you have read – this would not be technically challenging to implement – and then add a character who can be paid with in-game money (say, 100 gold?) to point you in the right direction. Not to give you a hint, I stress, but simply a system that can check what you’ve got, notice that you’ve got Item A and Item B and Piece of Information C and you have unlocked Area D, and then say to the player “You should go and look in Area D, and there you will find a puzzle you can solve”. No hints about the nature of the puzzle or what is involved, but simply information about a place you ought to look. Such a system would be a huge time-saver but wouldn’t really, I would argue, make the game meaningfully easier; it would just stop endlessly searching at times for something to actually do. Also, while the level design is generally excellent, a few areas I didn’t really enjoy spending time in. In particular the Graveyard of the Giants is truly obnoxious, even by the standards of a game that derives a lot of provocative player-mocking amusement by being obnoxious, and aspects of the Chamber of Extinction, the Tower of Ruin and the Inferno Cavern got on my nerves as well. Nevertheless, these are only minor gripes, but some of the areas in particular where sub-sections of that area, can only be accessed from another area, were frustrating and didn’t really seem to add much.

The art style and the music in the game, although never the focus, are also worthy of some mention. The visual style is absolutely lovely and all the roughly twenty areas in the game have beautiful and distinct aesthetics, including some interesting and unusual colour palettes one rarely sees in game and a real commitment to meticulous visual design and detail. Some of this detail of course factors into the game’s ridiculous puzzles, while some aspects are simply to add more complexity and more visual confusion and intricacy to the world which both really help to construct the sense of exploring the ancient ruins, and do some work masking where the puzzle solutions might actually lie. The graphics are really gorgeous and the world is just a total delight to move around and look at it (my point above about “where do I go?!” notwithstanding). The bosses in particular merit mention – almost all of them are very visually striking and very inventive, particularly some of the later ones. The music meanwhile is absolutely outstanding, a tremendous set of thirty or so tracks that really set the tone brilliantly for each area and after you’ve spent so much time in the game world, each theme really becomes integrally tied in your head to the feel and sense of each particular area. The boss tracks are all unique and excellent as well, and in this regard as in so many others one really gets the sense of what a labour of love this game is. There’s just so much effort put into every single part (looking at you, Elden Ring) to make sure that every location, every room, offers at least something of note in some way, even if it’s very mild or very subtle or not something that the player is likely to appreciate until much later in their playthrough.

While it had a few niggles I think could have been ironed out without losing much (anything?) of the experience, La-Mulana was exactly the sort of puzzle game I’ve been seeking and so rarely find and a real joy to throw myself into. It’s so unyielding, so absurdly vast in scope and ambition and the density of stuff to figure out and do and keep track of, so cryptic yet solvable, made with such dedication and care and attention, so confident in its harshness and its mysteries, and so rewarding to the player who truly realises that this is an all-consuming, all-demanding thing which is going to test them to the absolute limit. I find this game to be a truly fascinating and endlessly compelling artefact, and I confess that I have become addicted to watching blind playthroughs of the game. It’s absolutely fascinating to see the different approaches people take, the puzzles that some fine trivial and others find baffling, and just how many paths and processes of logic are available in this game for the player. It’s a stunning and uncompromising work, and the real stand-out from my 2022 gaming. What a fascinating, absurd, unique piece of work.

So:

There we go! What did you all play this year, and what should I think about playing next year?

Dwarf Fortress of course!

It might actually be the year that UFO50 comes out as well.

Heh, very possibly! And UFO50 – that’s a new one on me, but a quick Google later and it looks interesting, will definitely be keeping an eye on it.

Yeah, the release is so exciting! I’ve watched *so* much DF on YouTube / Twitch though my own play is pretty minimal. Maybe 2023 will be the year…

There was one game that pushed me to the next level of ambivalence this year. It’s called Unexplored 2. It’s extremely creative roguelike that amazes with art, concepts and ambition, but then that ambition is somewhat a downfall of that game, as the code can’t keep up, resulting on occasion in truly bizarre buggy quagmire. The game is fully released, but fortunately under very active development and I hope it will still come up a masterpiece in the end. It’s kind of a gem at this point.

Thanks for the comment Haemol! That’s a new one on me – I just looked it up and certainly looks interesting. If it *really* plays into that “the world is not permadeath but you are” thing, there’s definitely plenty of interesting stuff which could be done with that. Sad to hear it’s very buggy at the moment (the reviews I can see on Steam do seem mixed) but I’ll definitely keep an eye on it…

I enjoy reading these every year, thank you for posting! I’m always surprised at the huge variety of different genres of games that you play. I think we would get along, as I also love playing both mainstream and obscure stuff, and both new and retro.

Anyway, I found your Elden Ring review especially interesting. It’s practically impossible to avoid discussions and coverage on the game these days. I am apprehensive to try it, though my history with the Souls games is very limited compared to yours. I played about a quarter of Dark Souls 1 a few years ago and really loved it, though I’ve been meaning to get back to it. I also played quite a bit of the Japanese-only King’s Field on PS1 (a fan-translation), which I also enjoyed despite it being so incredibly archaic and clunky.

I tend to dislike open world games quite a bit, and it seems we agree on Skyrim…So reading your review seems to highlight some of my fears about Elden Ring, that it might betray what made other From Software fantasy games so great.

Also, I went back and read your “year in review” posts from previous years, which I haven’t read in quite a while. I see lots of great recommendations of games to keep my eye on. Thank you, Mark!

Thanks so much for this very kind comment Zack! I really appreciate you taking the time. Yeah, I definitely try to be a pretty diverse game consumer; I certainly spend more time with indie than blockbuster games these days, but certainly not exclusively.

That’s amazing you played King’s Field! I’ve often considered giving it a look myself. Open world games are likewise definitely not my thing – in many ways URR is sort of “what I’d want in an open world game” or me trying to make an open world game that I’d actually enjoy spending time in as a player – and Elden Ring really just hit so many of those wrong notes for me :(. Ah well. I’d definitely go back to DS1 if you enjoyed it, it’s… pretty extraordinary (especially if one can play relatively un-spoiled).

Anyway, I’m so glad you enjoyed the other ones too, thanks Zack! I’ve actually already started work on the 2023 one based on the first game I’m playing right now… (always best to try to get ahead of these big writing jobs!)

The best games I played this year were Into the Breach and Diablo 1 (both new to me). I found Diablo 2 and 3 to be very different, disappointing games compared to the first one. Into the Breach was amazing but I found the roguelite elements could have been taken out and I would have liked it more. Which surprises me to say, since I tend to love games with roguelite progression (Enter the Gungeon, Monolith, and Undermine are all great.) I stopped playing after my first winning run, but I loved it.

Mark, I’m interested in playing my first 4X space game. I know you’re a fan of Stellaris. Would you recommend that as a good place to start, or is there a classic title that would be a better jumping off point (maybe Masters of Orion?) I have no problem playing older titles from the 80s or 90s.

ITB I adore (the DLC will be on 2023’s list) and the Diablos I’ve never played myself, though I know a lot of roguelikey folk really enjoy them!

STELLARIS – yes, I think it’s totally amazing. The most recent big expansion was a bit of a letdown, but that’s only speaking as someone with ~800+ hours in the game, so that should be kept in mind. I think it’s a fantastic place to start, truly astonishing degrees of options for playing out every SF scenario one could imagine, and I’ve never actually played MoO myself. Your message though has got me interested in it – maybe it’ll be on the 2023 list???

The obvious suggestion would be La Mulana 2. I felt there was less ‘well, where do I find a puzzle?’ than LM1, and generally fewer frustratingly-designed areas.

But a better suggestion would be Tunic, which whilst being a pretty different game from La Mulana (if La Mulana is Maze of Galious-ish, this is Zelda-ish, circa SNES) manages to hit a lot of the really good exploration and puzzle points La Mulana (either game) did, generally without as many ‘well, where next?’ moment. It is very much a small-puzzle and large-puzzle adventure game.

It’s definitely on the list! I have begun playing it and enjoying it so far, though the early puzzles are definitely way kinder than the earliest puzzles in LM1, so I’m hoping it quickly ramps back up to the top difficult. Tunic – this sounds really interesting and I have added it to my list!

Hi Mark, long time reader/first time poster here. You may have sold me on La Mulana with the Outer Wilds comparison, haha. 1 suggestion and 2 sort-of suggestions.

1. Not a game, but another writer, Oliver Kiley. He writes about both board games and video games (often 4X). Here’s one of his insightful blog posts on categorizing board games by their core priorities – the thought process is really interesting. And his other stuff is great, too.

https://boardgamegeek.com/blogpost/27367/schools-design-and-their-core-priorities

2. Continuing on board games, Spirit Island (solo/cooperative) is really good – it’s got a ton of variety, and almost all the decisions are difficult (there’s little chaff). I don’t think you play many board games, but this one has a Steam app too.

3. Not an absolute recommendation, but Toki Tori 2 is somewhat interesting. You have movement and 2 abilities (chirp and stomp) that have different uses for most objects/creatures in the world. I think some people exaggerate how open-world and not hand-holdey it is, but there’s still a good bit of discovery in how the systems interact. And in some cases, figuring out the goal of a level is part of the challenge, and it has to be done before trying to achieve that goal. Not quite Outer Wilds, but still interesting.

Hi there Henry, thanks so much for leaving the comment! Yeah, LM is bonkers but strong OW vibes in terms of the puzzles. It’s definitely a harder game (and OW is not trivial) but not ludicrously so, I think.

1) I will definitely give this a look! I’ve heard of the site but being not a huge board games person I hadn’t really looked into it much until now. That’s an interesting article though, I’ll be sure to read some more (especially on the 4X stuff).

2) Thank you for this one! I am getting slightly more into board games so I’ll keep this one on the potential list for the future (right now I’m really enjoying Wingspan a great deal – hits the exact luck & skill & many ways to win sweet spot for me).

3) Ahhhh yes, this. I’ve come across this but haven’t played it yet – I do love games with interesting and complex systems you figure out – hence why Rain World was such a joy – and it definitely interests me. Thanks for bringing it back up to the top of my brain – this may well be a 2023 game for me.

Hey, great to see the game progress!

Now, since you asked for recommendations:

If you haven’t played Disco Elysium yet, you should fix that. It gets categorised as an RPG usually, but really it is a Point-and-Click adventure game wearing the skin of an RPG in order to sneak up on you. But that’s okay, becuse the world building is sprawling and New Weird-y, the character writing and voice acting is top-notch, and the art and music are quite lovely.

Old World was my GOTY with a fresh take on the Civ-like genre that took Crusader Kings style events and enmeshed them quite cleverly into the main game mechanics. Also the AI knows how to play the game. So that’s my second recommendation.

Thanks so much for the comment Jeff! DE is absolutely on my list and I’ve purchased the thing, I just haven’t played it yet. It does sound like something I may well massively enjoy though from what I’ve read about it, so I’ll definitely be giving it a look before long. Old World I confess I actually hadn’t even heard of, but I like the description you’ve offered here. I shall look into it…

Two small team games where the ones I loved most.

Highfleet: ¿A fleet management sim? ¿Twin stick physics shooter? I can’t describe this game properly, but it’s a really competent military drama, where you lead a desperate beheading strike, in an attempt to negotiate in a losing war.

The art direction is great, the writing is concise but impactful, and some plot moments are unmatched in my videogame experience.

The game is also a game of psychological warfare. Against you. A single screen map, where radar alerts, infrared detections and intercepted radio messages give you hints of imprecise information about all the fleets hunting you. Everything tales time: navigating, fueling, repairing, rearming.

There’s an interesting character developing system, with some ethics (kindness, fear, faith, loyalty, greed) that reflect not your personality, but your reputation among your crew. How THEY see you. And there’s no “bad” ethos.

Rain world: I don’t like “metroidvania” games. I don’t like the progression blocking.

This is a game where you can do anything from the beginning. No new moves, no better weapons, no secret vision. It’s not about that.

You never “level up”. Instead, you get to understand the ecology and how to traverse / survive this strange beautiful abandoned world. You will survive if you adapt, not if you fight.

The moment I understood that was after a lizard hunted me, and the game suggested “push to go back to savepoint”. Just suggested. But the lizard kept its way to its lair, and I was curious and the zone was gorgeous to look at.

Then, a different lizard appeared, and challenged my hunter for its food (me).

They clashed togegher and my body was trown aside and… It got up in its tiny feet.

¡It was playing dead! Like every prey does in reality. I ran away and found a refuge and it became the moment I understood what this all was about.

Later on, the wonderful music and the mistery of a ¿Story? Got me hooked until the end. But I learned a few things and explored the most melancholic, beautiful, not-dead-at-all world.

It’s haunting, and beauticul, and I’m so glad I discovered it by chance.

Alberto, I am so sorry I somehow missed this comment at the time! Absolutely hopeless, I do apologise. I don’t know whether it’ll send you an email update when I post this reply, but I hope it does. Anyway – thank you for the Highfleet recommendation! It sounds really interesting and I have added it to my wishlist. Rain World, we agree, is a weird masterpiece – totally wonderful. Thank you again for the comment!