A Hunter is a Hunter, even in a blog entry…

Regular readers of my blog may remember a comment I made a while back about a game I’ve been deeply anxious to play for some time. This was Hidetaka Miyazaki’s new masterpiece (or so the reviews told me) – Bloodborne. I know I’m rather behind the times here, but these days I have so many obligations of various forms that finding the massive chunk of time required to really delve into a “Souls” game is not an easy task. A couple of months ago I had a week off work ill, and this seemed like the ideal time to get started. I didn’t finish it in those five days, and didn’t even start the Old Hunters expansion, but I got through a good 80% of the main game in that period. In the weeks following I added in a couple of hours each evening every three or four days, completing all the main game content; I then tackled the Old Hunters DLC over the next few months. Having now \completed pretty much everything that can be completed in one playthrough, I thought it was time to write up some thoughts, a lot of which are very relevant indeed to the study of PCG systems, and indeed to the kind of game that URR is turning into.

This isn’t a review – briefly, I thought it was another absolute masterpiece of storytelling, level design and gameplay mechanics that combined to form a worthy (spiritual) sequel to Demon’s Souls and Dark Souls, although it was not of course without its minor flaws – as this entry is instead a look at a rather surprising aspect of the game, seemingly out of place in a series known for its intricate handmade placement of every single element. Which is to say that Bloodborne (many spoilers ahead!), for those who don’t know…

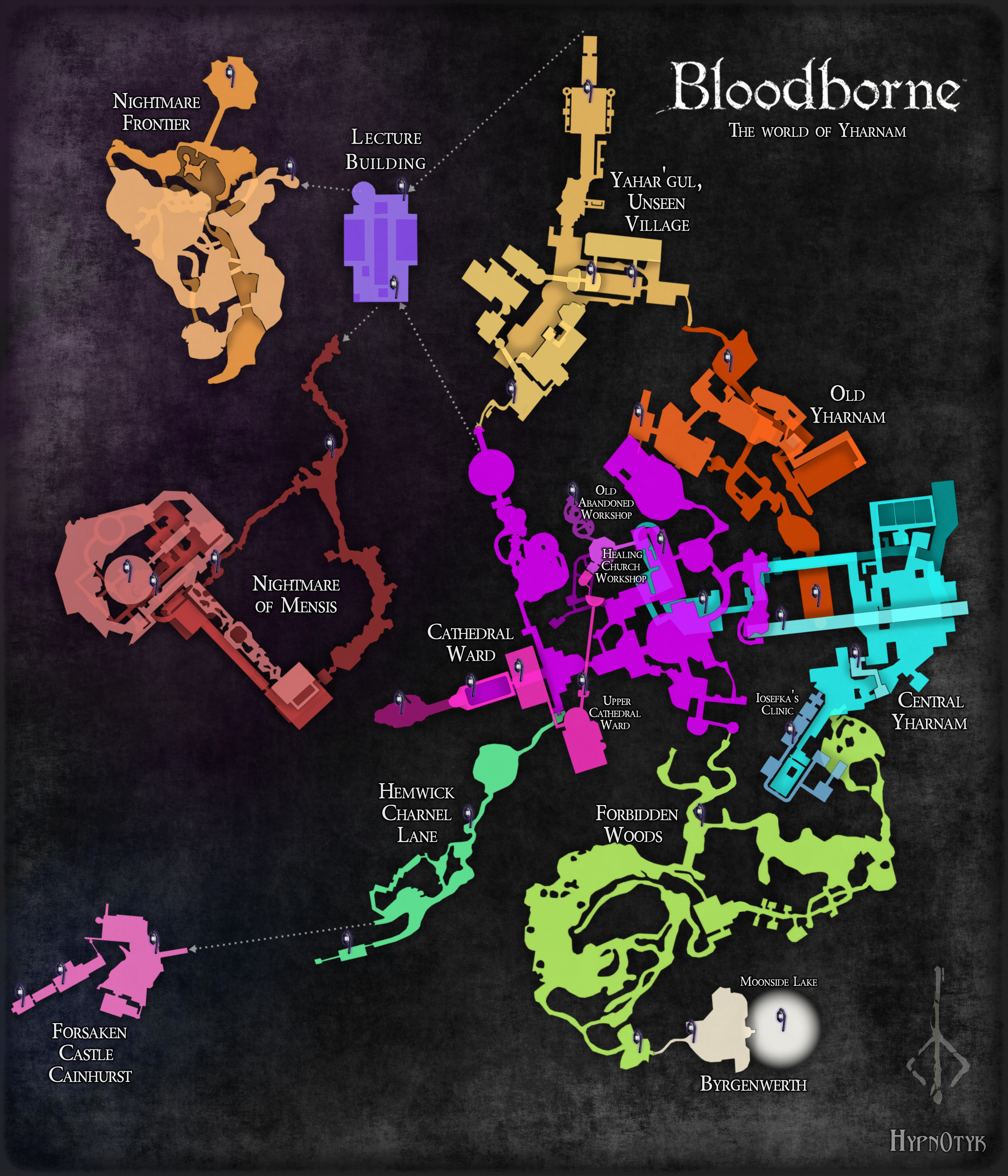

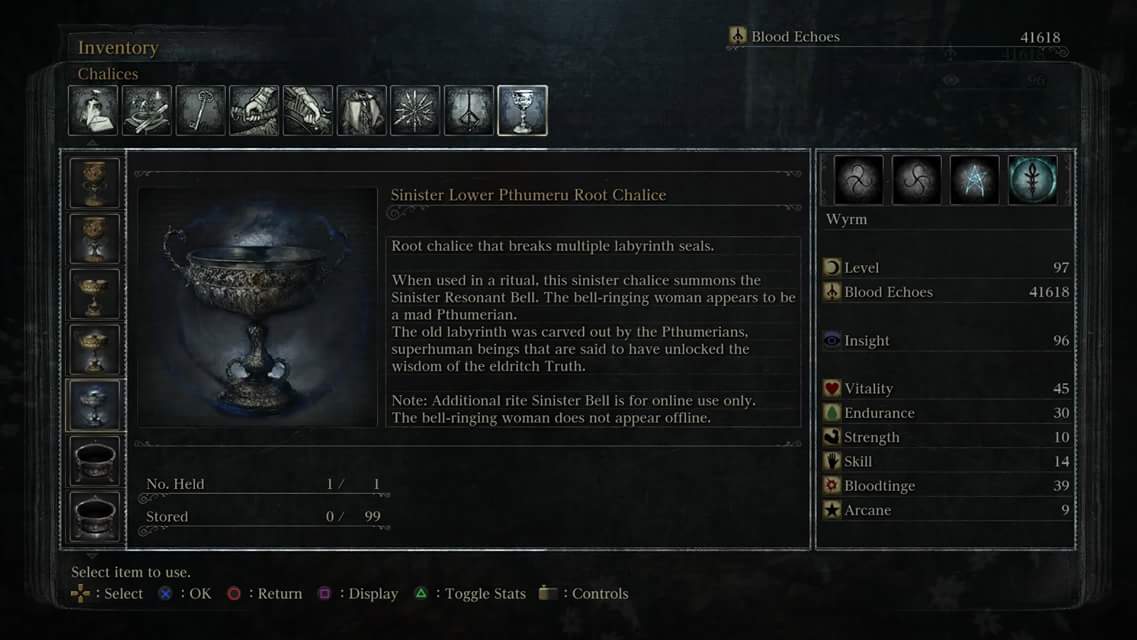

…is full of procedurally-generated regions, known as “Chalice Dungeons”. Not all are PCG, but those which are not use the same tiles, building blocks, enemies, items, and so forth, as those which are. One gains access to these part-way through the storyline (I think I gained access for the first time quite a bit later than intended due to the path I took, since I defeated the Bloodstarved Beast after I’d entered the Nightmare Frontier) and they basically place a selection of rooms and corridors across several floors, chuck a boss at the end of each floor, and fill them up with enemies of various types and items that cannot be found in the main game, or sometimes items that can, but are very rare. A number are fixed, but the overwhelming majority – which is to say, an effectively infinite number – are procedurally generated. In these dungeons one can also locate a small number of “lore” fragments that cannot be accessed in the main game. There are also a number of items required to unlock harder Chalice Dungeons, which only spawn within earlier Chalice Dungeons, thereby encouraging the player to progress logically through them rather than leaping immediately to the ones at the end (although if, like me, you come to Chalice Dungeons quite late, the earliest dungeons can seem bizarrely simple compared to the horrors you are facing elsewhere). Although in principle one might think this concept – infinite Soulsborne! – is quite promising, I find the Chalice Dungeons to come with a particular set of issues that are worth examining, specifically with regard to the particular kinds of PCG they deploy, and the stark contrasts between this PCG and the rest of the Bloodborne world. It is these tensions I want to unpick in this piece, as I think Bloodborne makes for a fascinating example of how PCG intersects with other elements of game design, and should always be seen in context rather than as simply a number of possibilities or a length of time it extends the anticipated gameplay.

Meaning and the Unknown.

“Soulsborne” games have always, for me and I know for many players, hinged on two things – the fascination of not knowing what bizarre thing is around the corner, and knowing that whatever is around the corner is guaranteed to have some deeper meaning. This applies whether it’s a massive skyline-dominating structure or simply the kind of clothing on a corpse. If we look at the first of those factors and ignore the “meaning” component for a moment, it seems somewhat logical to attempt to extend a Souls game into PCG. These are games that already thrive on the player’s exploration and discovery of the unknown, whether spaces, lore, or gameplay mechanics. Having also gone even further and given Bloodborne an overall literary inspiration that emphasizes the unknown (more on this later), going the whole way and adding an element of constant and guaranteed unpredictability to parts of the game world might seem like the obvious third component. One might think that adding a PCG element to a game of this sort would enable the designers to consistently and constantly recreate that feeling of exploring the unknown, and of not knowing what’s around each corner. Integrating this with the narrative and game mechanics (which Bloodborne does try to do) appears extremely sensible. However, this didn’t, I feel, work as expected.

The Uninteresting Unknown

The first problem is that the “unknown” within Chalice Dungeons simply doesn’t seem to be that interesting. There is not a particularly massive set of possible rooms (as far as I could tell after some, but not a truly exhaustive, amount of investigation) and few of the rooms are especially fascinating; there are lots of standard corridors, lots of areas that just have some pillars and some enemies, and so forth. I encountered a couple of gigantic “special” rooms, which are much more exciting, but by that point the Chalice dungeons as a whole had (sadly) already failed to hold my interest. There was no point that I felt I was going to turn the corner and discover something truly exciting or important to the lore. Although I naturally adore the difficulty level of these games, the worldbuilding and lore are probably the main thing I play Souls games for. Bloodborne also seems fond of producing dead-ends that contain minimal loot of any real value, which is surprisingly infuriating. I was actually surprised at how annoying I found this – maybe I’ve become used to PCG games either a) not generating dead-ends, b) generating dead-ends of value, or c) generating dead-ends but having an auto-explore system. The lack of any of these made these dead-ends aggravating and actually discouraged me from exploring. I found myself basically sprinting through every single Chalice dungeon I played and trying to find the boss door, remember the location of the door, find the lever that opens the boss door, pull the lever, and then sprint back to where I started as rapidly as possible in order to progress to the next floor. In a similar vein, the game didn’t always place something in a location where, if the level had been hand-made, something would definitely be. I recall a massive room with a balcony that ran all the way around the upper level; if memory serves, I explored the full upper balcony, and found not a single connection, despite wasting close to a minute running around the thing, subconsciously thinking “this would never be pointless in a normal Souls game”, which is to say, one that is entirely handmade.

The Lack of Meaning

The second problem is the lack of meaning, as well as the lack of interest. The only things I could find in the Chalice Dungeons with any actual lore significance were the bosses and a very small number of items (several of which I’d already found outside the Chalice dungeons), and that was it. As far as I could tell the placement of nothing mattered, and the enemies seemed to have been selected to populate the dungeon I was in largely at random; there was none of the thematic consistency in enemy selection I expected (and got) from the rest of the game. I didn’t feel at any time as if I was exploring a region that was in any way connected to the rest of the game. Even areas of the main game you have to effectively fast-travel or teleport to, like Cainhurst Castle or the Nightmare Frontier or the Nightmare of Mensis or whatever, all still felt without doubt as if they were part of the same fictional world. This just felt like a level in a computer game, which is a feeling the Souls games have always been amazing at avoiding, but the Chalice dungeons just really brought me out of immersion in the world and reminded me that I was playing a game, and that this area had just been procedurally generated a moment before I set foot in it and had no longer, deeper, lasting meaning.

Handmade PCG Worlds

These two elements combined to leave me completely cold when it came to the Chalice dungeons. However, the more I analyzed my own feelings on this matter, I realized that I was inevitably coming from a very particular perspective. I have, in essence, spent several years of my life attempting to create PCG systems which don’t look like PCG when you look at them; or, to put it another way, to create PCG systems which are always interesting to explore (because they appear as if handmade) and always seem to have meaning to them (because they are connected to the wider generated world). I’m therefore probably coming to Bloodborne, more than perhaps almost anyone else on the planet, from a perspective of making PCG systems designed to be a) endlessly interesting and b) to have the kind of deeper meaning and world-connectedness we expect from everything in a Souls game. Looking back, this probably made me a tad more negative than I would otherwise be, having become to used to my own work and then being sharply reminded that not all PCG systems are like this – a contrast, of course, made more extreme because the hand-made parts of Souls games are like that, and is precisely those feelings in Souls games I’m so keen to recreate in URR. This aspect isn’t a severe criticism, of course – From Software have never really done any PCG stuff before and it isn’t the core of the game, whereas I’ve been coding and thinking about little else for several years, so there is naturally going to be a little bit of disparity when it comes to the quality of meaningful PCG systems – but I still couldn’t escape such a perspective. I have come to expect such a high quality of game design from them (Dark Souls II being a freakish aberration) that finding an area that failed on both the things I look for in Souls, i.e. meaning and the interesting unknown, was an unpleasant surprise.

Too Many Bosses Spoil the Dungeon

Another strange factor in the Chalice dungeons were the bosses. There were two issues here: ease, and volume. By the first, I mean that every boss I fought in the Chalice dungeons was extremely simple. Now, I know that later bosses can include some of the toughest bosses from the main game, but the first six Chalice bosses were either a) bosses I hadn’t encountered in the main game, and were trivial, or b) bosses I had encountered in the main game, and were trivial. In the main game bosses are almost always this very important moment in the player’s progression, a substantial challenge and something to be seriously strategized over. This is certainly true in Bloodborne, with quite a few notoriously challenging bosses thrown into the mix to trip up the first-time player. However, by giving me such easy bosses, they barely even felt like bosses at all, and more like a couple of slightly-tougher-than-normal enemies. This was exacerbated by the volume of bosses – each Chalice dungeon has three, and that again served to make them feel very unimportant in the grand scheme of things because I went so rapidly from one to the other, whilst one can go hours and hours without encountering a single boss in the main game. In fact, the same can even be said of the lanterns! For those who don’t know, rather than “bonfires” as checkpoints in the Souls games, the equivalent in Bloodborne are “lanterns”. In the main game these are deeply rare and deeply precious things (as they were in DS1 and I’m told they are in DS3), but in the dungeons you run into half a dozen in every single Chalice dungeon. This, again, had the exact same feeling of trivializing everything I encountered, because I had become so used to the sense of victory and relief upon finding a rare lantern that finding tons all over the place made the Chalice dungeons, once more, not really feel like a part of the game, but this poorly-thought tacked-on addition where everything was quicker, simpler, and lacking in any of the importance, consequence or weight of the main game.

Cosmic Horror and the Unknown

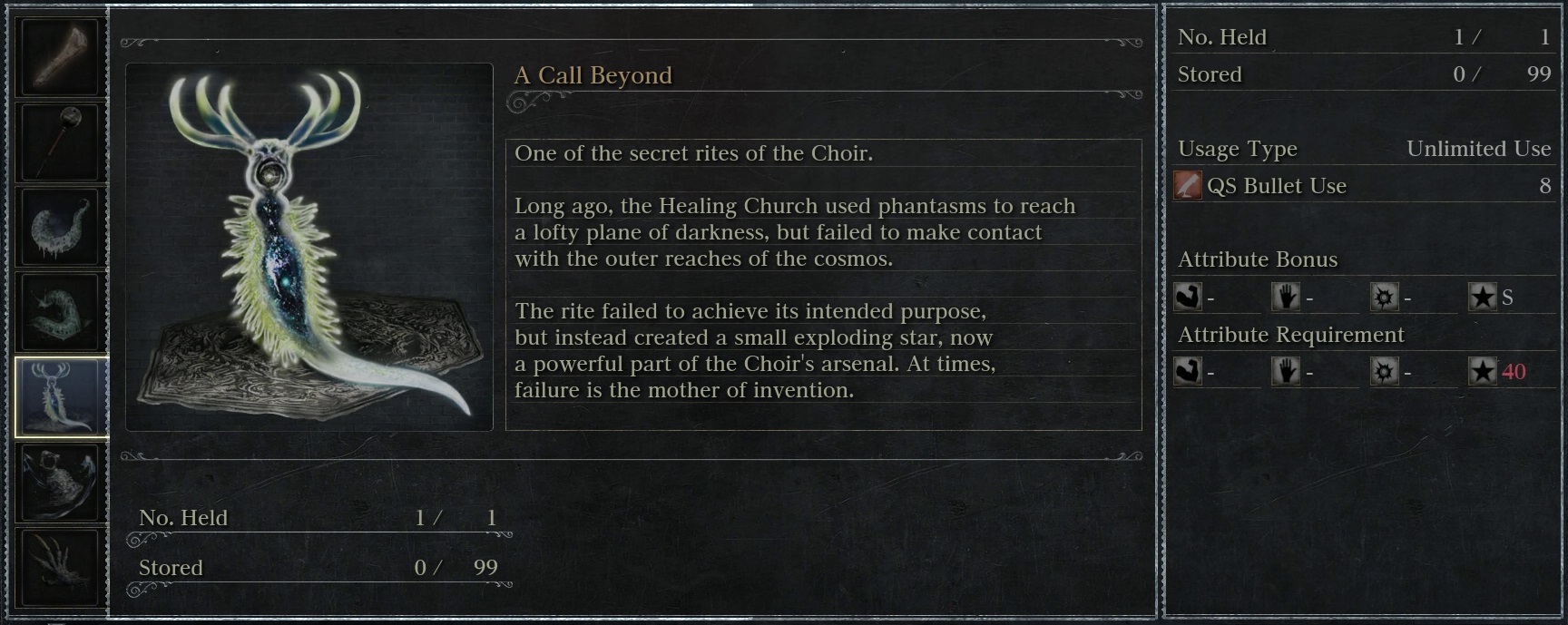

Now here’s the really interesting thing. Although Bloodborne presents itself a primarily Gothic horror, as the game progresses it becomes increasingly apparent that there is a deeper layer of Lovecraftian/”cosmic” horror. There are hints to this in the earlier parts of the game – the odd mention of “the Great Ones”, some rather unsettling statues in the lower level of the Cathedral where the player fights Vicar Amelia, a few references to madness and knowledge (classic cosmic horror themes!), and so forth – but for the most part the boss encounter with “Rom, the Vacuous Spider” at the bottom of the lake, and the subsequent appearance of all the Amygdala creatures in the Cathedral Ward, signals a very explicit pivot to the player’s ability to now see that which was hidden previously in the game. The game ceases to be only a Gothic horror – although it is still Gothic in a broader sense as a way of delivering a complex, twisting and expansive narrative – and immediately shows its true colours and lets the player glimpse some of the cosmic horror hidden beneath the surface, whilst still naturally keeping a lot of questions and secrets – since a) this is a Souls game, and b) Lovecraftian horror hinges on secrets/mysteries/never saying too much.

Now, naturally reading a novel is also about “the unknown”, as is experiencing a food one has never hitherto experienced, or going to a previously-unvisited country, and (to a greater or lesser extent) all of life’s pleasures are, in one way or another, about experiencing the unknown. All of this is true, and there are certainly philosophies out there (Nietzsche, Deleuze, Malaby, Taleb, etc) who deal extensively and usefully with the place of the unknown and the unpredictable in human life in various ways (see also, naturally, my upcoming first academic book). However, both PCG and cosmic horror have a particular emphasis upon the unknown, for the construction of their core gameplay challenge or their core narrative conceit, respectively. Bloodborne didn’t only bring PCG to the table for the first time in a Soulsborne game, but it was (pretty much) the first time that a cosmic horror element was also introduced. At this point it’s worth taking a closer look at cosmic horror and exploring its relationship to PCG in Bloodborne a little more, and why Bloodborne (sadly) falls down at integrating the two.

Cosmic in this sense, of course, doesn’t refer to the mechanical orbits of planets and moons we now know they inscribe; cosmic instead refers to something more like the feeling we get upon considering astronomical distances. We can be told the distance between two stars, just as we can be told in a cosmic horror novel about a particular eldritch creature, but just as human brains aren’t really equipped to truly understand what a billion billion kilometres actually means, in exactly the same way we aren’t really equipped to grasp the creatures we are interacting with – they are simply beyond our comprehension, no matter how much about them we are told and shown. However, since these creatures are not real (one hopes…) and the author cannot rely on genuine cosmic horror to evoke the appropriate feeling in the reader, this sense of being beyond human comprehension is instead depicted by limiting the amount of information given about these dread abominations, the idea being that the characters are unable to perceive or understand certain aspects, and therefore those aspects are not related to the reader.

Cosmic horror has been visually depicted surprisingly rarely – I think part of the reason is that no matter what we see on the screen, it can never evoke the direct horror described in cosmic horror stories, because we don’t know of anything immediately physically present that could actually, in the real world, evoke the same feeling of nausea in us as cosmic distances. Bloodborne gets around this, partly by showing relatively little, partly by leaving a reasonable amount unanswered, and partly by leaving the player to put the pieces together and try to understand the true horror of the situation – as the imagination, of course, is far more powerful than any kind of graphical fidelity in this kind of situation.

How does this connect to the Chalice dungeons? Two ways, I think:

1) Firstly: you can see everything. There are no mysterious eldritch horrors there; you find motsly enemies that you’ve already encountered in the main game, and none of the new enemies or items particularly evoke any real sense of mystery. So much of the “story” of the main game is unspoken and has to be pieced together, but in the Chalice Dungeons one never gets a sense of any of those secrets lurking behind every wall and every enemy. They are very physical, complete, singular, monolithic, and – since you teleport into the entrance of each one and back out at the end – feel very far apart from the rest of the world. The dream and nightmare lands of the main world avoids this through a range of clever tricks (which are an essay in their own right), but sadly, the Chalice Dungeons don’t (or, rather, can’t) use these same methods to add mystery.

2) Secondly, the problem is that nothing in the Chalice Dungeons (in sharp contrast to the main game world) has anything of the mysterious weight that so much in the main game world has. This kind of mysterious weight – of things deeply ancient, deeply unknown, of things we only know fragments about – is central to cosmic horror, and nothing more than a quick look at how rituals, books, and artefacts are talked about in Lovecraft and his successors will illustrate this point. Nothing in the Chalice Dungeons feels truly old, and the combination of teleporting into these dungeons, the knowledge that many are PCG’d, the lack of narratively-relevant placement of items, and the repetition of bosses, makes them feel passing and surface, rather than deep and eldritch.

Finally, let us compare the Chalice dungeons to some other “infinite dungeons” – here I think the Abyss and Pandemonium in superlative roguelike Dungeon Crawl Stone Soup are the most useful points of comparison (and, for the reader wishing to explore other versions of the same idea, require them to master only one roguelike instead of several!). For those unaware, the Abyss is an infinitely-sized dungeon spread over five floors, each of which becomes more twisting and bizarre as one descends. Pandemonium, meanwhile, is an infinite set of floors, some of which are special and contain hand-made elements alongside their PCG elements, whilst the others are fully procedurally generated. The Abyss succeeds so well as an infinite dungeon area for several reasons. Firstly, it has a far higher range of variations than the Chalice Dungeons, with a mixture of totally PCG and fixed elements, and the interactions between these (and the generative system more broadly) can create a huge range of options, keeping things fresh for a long time even when played by experienced players. Secondly, the fact it constantly shifts takes the lack of “solidity” that one can sometimes feel about somewhere you know has been generated, and rather than this working again the feeling of this being a meaningful place, DCSS turns it into an advantage – it feels believable that somewhere constantly changing and shifting would be infinite and size, and the parts that do not shift come to feel more important when they stand out from the part that don’t. Pandemonium, similarly, lets the player explore an area which feels it has weight, whilst also being effectively infinite. It does this through (again) a greater number of component parts, and the randomness of when one will encounter one of the powerful “Pandemonium Lords” who wander the domain and have their own private fiefdoms (giving a narrative sense of Pan being a place of flux, and change, and activity behind the scenes that the player doesn’t see). I think we should also say something of difficulty: it is easy to come to Chalice Dungeons over-levelled, and have this influence your experience, whereas it is hard to reach the Abyss truly over-levelled (as many of the enemies are dangerous or non-trivial for all except the most incredible character builds), and almost impossible to reach Pan over-levelled (again, except for the world’s best DCSS players who know how to build their characters in such a way as to survive Pan with high confidence). For the average or even high-skilled player, reaching these areas when truly over-levelled will never happen, and thus you will almost never get the experience of simply rushing through them, which consequently makes them feel all the more transient. (And, of course, in permadeath games, all decisions and explorations always have more weight anyway).

Problems of the Chalice Dungeons

So what does all this mean? Well, I deeply appreciate Bloodborne’s attempt at interesting PCG content, and certainly well-implemented PCG in a “Soulsborne” game could have been something totally spectacular, but it just didn’t work out in the slightest for me (though that in no way impinged upon my enjoyment of an otherwise astonishing game). Once I’d done a few Chalice dungeons (and checked on the Wiki that they were non-essential) I have only returned with a friend, not for their “own” sake (although we might do a Roguelike Radio episode on them one day!).

Ultimately, there are five issues here. Firstly, the components of the Chalice dungeon generators simply don’t seem that interesting, and lack the feeling of excitement at turning the next corner I expect from a Soulsborne game. Secondly, those same components tend to lack any actual meaning or importance within the game world, and are chucked together (broadly speaking) at random. Thirdly, from my own perspective, this attempt at procedural generation in a game notorious for its stunning hand-made worlds resonated poorly in light of my own current endeavours to “fake” a world with handmade detail, via PCG. This is an unavoidable bias, and one that I think needs acknowledging, but even if I wasn’t making URR I would certainly have felt the same way overall, though perhaps somewhat less acutely. Fourthly, the endless flow of bosses and lanterns in the Chalice dungeons served to further “trivialize” them because they stood in such sharp contrast to the rest of the game world. Fifthly, the generally mundane and passing nature of the Chalice Dungeons stand in sharp and unfortunate contrast to the rest of the game with its complexity, intrigue, and narrative weight. Although a brave attempt at adding something new, and I do think with some work this could be a very promising path for a future game, their implementation in Bloodborne makes them feel very weak compared to the rest of the game, and sheds some interesting light on how the technical elements of PCG (and the dungeons’ component parts), and the context of the narrative and lore of the rest of the game, fundamentally intertwine.

Bloodborne Micro-Review

As I say, this did not detract from my overall enjoyment of the game. Bloodborne might actually be as impressive a piece of world as the original Dark Souls – extremely tight central mechanics, constant surprises and discoveries and points of amazement, a million strategies to pursue, an almost absurdly detailed world conveyed through dialogue, description, aesthetics and atmosphere (so, who else spotted that the oil lamps in the Fishing Hamlet are lit by the slugs/phantasms they’ve dredged up, for instance?), and an amazing dialogue with a range of literary traditions (as opposed to the predominantly mythological in Dark Souls). It, like Dark Souls, is a world that feels so real it can be hard to leave. I have no idea why I do this, and I’ve probably lost a good two or three hours of my life in total, just running around the “Hub” areas of these games doing absolutely nothing because I didn’t want to leave these stunningly drawn, detailed and resonant worlds. Bloodborne has done this to me again, and I confess to wasting a worrying amount of time just being in it without actually doing anything especially useful. Bloodborne’s an astounding game, but the Chalice Dungeons – although the concept does have potential – are certainly its weakest part, and stand out all the more from the incredible strength of the rest of the game. To anyone who has not yet played Bloodborne, I recommend it in the strongest possible terms. However, if you’re reading this blog, there’s a good chance you have an interest in PCG. As such, I would just suggest that you don’t expect too much from the game’s procedural elements, but rather immerse yourself instead in the wonders to be found outside the Chalice Dungeons, as you will not be disappointed.